Little or no interest in progress?

Great Britain and the Bauhaus

What influence did the ground-breaking ideas of the Bauhaus have on British architects and designers – and which role did modernism play in the tradition-conscious Empire? In view of the general election on 8 June 2017 we turned our attention to Great Britain.

[Translate to English:] headline

The industrial revolution in the latter half of the 18th century led to a radical transformation of society, not only in Great Britain, its country of origin: The resultant industrial society also brought lasting change to the living conditions of people in the rest of Europe and in the USA. In Great Britain as early as the 19th century there was already resistance – not only in politics, but also in the arts – to the effects of the rapid growth of mass production.

In ca. 1870 a group of young artists influenced by the poet and Designer William Morris and the art historian and philosopher John Ruskin brought the Arts and Crafts Movement to life. This design movement called for a return to the crafts and placed an emphasis on joy in the work of the artist and the natural beauty of materials. In the fifty years thereafter the Arts and Crafts Movement not only established itself in Great Britain and the USA, but also spread from there to a number of European countries and eventually to Japan.

[Translate to English:] headline

The idea of valuing products crafted by hand above industrial mass production was regarded as the British response to the changes wrought by industrialisation. Many years in advance of the Bauhaus, the Arts and Crafts Movement already pointed to the simplicity of design and the significance of craftsmanship as an ideal unity of artistic design and material production.

The financial crisis triggered in autumn 1931 and the resulting monetary crisis forms a significant landmark in the development of British architectural history. In view of the straitened circumstances of thousands of citizens, numerous established members of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) turned their attention to the urgent concerns of town planning, redevelopment and housing. The concept of the Bauhaus, which had already come up with constructive solutions to these problems, slowly found favour with British architects. [1]

[Translate to English:] headline

In May 1934 Walter Gropius travelled to London on a trip arranged by Moholy-Nagy, where he was invited by the RIBA to speak (for the first time in an English-speaking country) at the opening of an architecture exhibition. At this time, both Gropius and the Bauhaus’s ideas were already known in British professional circles. [2] After the inaugural speech by the then president of the RIBA, Sir Raymond Unwin, Gropius delivered a lecture on Peter Behrens (the “leading representative of industrial design”), the minimal dwelling and the “replacement of slums with new housing estates”. [3]. In addition, around 170 of Gropius’s photographs and drawings of exhibition, factory, theatre and residential buildings were shown and passionately discussed by the RIBA architects. [4]

Just a few days later Gropius’s theories were published in the RIBA Journal. In the same issue, Gropius’s essay was directly followed by an introduction to a book titled ‘Who will deliver us from the Greeks and Romans?’ This critique focused more on art than on architecture; however, some participants were delighted by this juxtaposition and saw it as a challenge, rather than pure coincidence. [5]

[Translate to English:] headline

In order to better illustrate the ideas of the Bauhaus, the RIBA Journal showed on its frontispiece the Gropius-designed residential buildings in Berlin-Siemensstadt. It described the content of the lecture as “magnificent” [6] and called on its members to take on the new ideas with “openness and a thirst for knowledge” [7] : “Even if it is to be neither desired nor expected that the whole of England now erupts into wild enthusiasm about a way of building and of designing that clearly runs contrary to the wishful thinking of most of the architects and people of England […]”. [8]

[Translate to English:] headline

On the basis of assurances from Maxwell Fry and Jack Pritchard that they would realise building projects together and due to the ongoing difficulty of getting contracts in National Socialist Germany, a little while later Gropius left his homeland for London. It soon became clear that just a small circle of architects, building contractors and specialist journalists were open-minded about the modern methods of design and construction and design vocabularies. [9] An inadequate grasp of English and complex conversions from German to British standards presented additional challenges in everyday professional life. Gropius, who essentially felt at ease in British society, also complained of the younger generation’s lack of interest in innovations and changes for the future. [10]

British architecture in the 1930s was in fact still largely based on architectural forms that dated back to the turn of the century. It is notable that British architects were not represented at the founding meeting of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1927, or at other notable architecture events such as the Weißenhof housing estate exhibition in Stuttgart in the same year. [11]

In 1932 the American architectural historians and architects Henry-Russell Hitchcock und Philip Johnson drafted the following appraisal in the Modern Architecture exhibition in New York: “In [...] England really modern architecture has only begun to appear”. [12] And in 1937 Berthold Lubetkin , a Russian émigré architect who as co-founder of the architectural practice Tecton was to become one of the pioneers of British avant-garde architecture, stated: “The whole architectural scene is fundamentally different from that of other countries […] , there is little or no interest in progress.” [13]

[Translate to English:] headline

These brief statements illustrate how difficult it was for many of the émigré architects to integrate themselves in the British architectural scene. They were frequently confronted by anti-modernist attitudes, or viewed as a threat to the British architects. Even the founder of the Bauhaus, by then internationally renowned, initially had to contend with reservations. Only his excellent reputation and good contacts eventually ensured that he was able to develop twelve projects in two and a half years. Four of these were actually realised, among them the Levy house in Chelsea, London (1936) and the Impington College in Cambridge (built 1935 to 1939).

[Translate to English:] headline

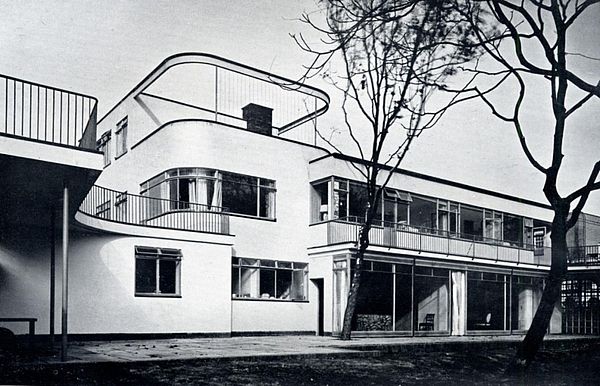

Both projects reflect concepts central to Gropius’s work, including echoes of “white modernism” in Levy house in the form of a flat roof, rendered facade and rounded balcony, and the emphatic horizontal lines of the Impington College, where the light-filled classrooms and the large foyer serving as a communications centre show clear indications of Gropius’s influence. [14]

Despite the realised buildings, Gropius did not settle in Great Britain. In 1936 he wrote to a colleague: “This is not a home; it is just a place to stay a while”. [15] Consequently, he left England just a year later. Gropius, whose main aim was to further the ideas and pedagogical concepts of the Bauhaus, moved to the USA, where it seems he finally found the right living and working conditions to deliver, after Germany, also the world from the Greeks and the Romans.

[NF/AW 2017, Translation: RW]

- [1+4+5+10] cf. Reginald R. Isaacs, Walter Gropius, Der Mensch und sein Werk, Bd. 2, Teil 2, Die Jahre des Übergangs, pp. 673-825.

- [2] cf. H. G. Scheffauer, The Work of Walter Gropius, The Architectural Review, Bd.66, 1924, pp. 50-54.

- [3] Reginald R. Isaacs, Walter Gropius, Der Mensch und sein Werk, Bd. 2, Teil 2, Die Jahre des Übergangs, p. 676.

- [6+7] Reginald R. Isaacs, Walter Gropius, Der Mensch und sein Werk, Bd. 2, Teil 2, Die Jahre des Übergangs, p. 679.

- [8] The Royal Institute of British Architects, Journal, Ser. 3, Bd. 97, 1955, p. 155.

- [9] cf. Andreas Schätzke, Deutsche Architekten in Großbritannien: Planen und Bauen im Exil 1933-1945, Edition Axel Menges GmbH, 2013.

- [11] cf. Dennis Sharp, Gropius und Korn. Zwei erfolgreiche Architekten im Exil. In: Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, p. 203-208, S. 203.

- [12+13] Berthold Lubetkin, Modern Architecture in England. In: American Architect and Architecture 2/1937. p. 29-42

- [14] Burcu Dogramaci, Scheitern und Bestehen in der Fremde. Deutschsprachige Künstler im britischen Exil nach 1933. In: Der Künstler in der Fremde. Migration-Reise-Exil. Uwe Fleckner, Maike Steinkamp und Hendrik Ziegler (Hg.), pp. 265-281.

- [15] Letter from Walter Gropius to Max Burchard, 21. June 1936, Berlin, Bauhaus-Archiv, Nachlass Walter Gropius,GN 8/81.