Prussian Islands in an Oriental Sea

International Modernism: Israel (Part 1)

The White City in Tel Aviv is regarded as the world's largest collection of buildings from the classic modern era. Many of them were built by former Bauhausler. But the origins of the modern movement in the Holy Land reach far beyond the Bauhaus.

[Translate to English:] headline

In an unremarkable place, a drawer in Tel Aviv’s city archives, the hand-coloured perspective view of a site plan has been lying for more than a hundred years. This view was originally meant to form the basis for the urban design of the Jewish residential district of Achusat Bajit on the edge of the city of Jaffa. It is dated 15 April 1909 and signed by Wilhelm Stiassny.

Two things are notable about this. First: only four days earlier, 60 members of that very same agricultural cooperative, Achusat Bajit, had gathered to dispense amongst themselves 60 previously subdivided plots with the help of an equal number of seashells. Second: the architect Wilhelm Stiassny was already 66 years of age when he signed the plan and could already look back on a noteworthy career in Europe. In the course of his professional life, he had not only erected synagogues in the neo-Islamic and neo-Romanesque style between Prague and Budapest, but also secular buildings such as schools, factories, cemetery halls and more than a hundred residential buildings in Vienna.

And now he was submitting the master plan for a residential neighbourhood that architectural history would later identify as the birthplace of the city of Tel Aviv. Wilhelm Stiassny was never able to witness this, however, because he died only three months after having signed the site plan in question. Tel Aviv was to be built by others, and because Haifa and especially Jerusalem were at the forefront over the next 25 years, architecture of consequence would not appear for some time.

Herzl’s visions

The anti-Semitic climate of 19th century Europe prompted the Jewish writer Theodor Herzl, who until then had only achieved moderate success, to write down his thoughts in a book. It was called “Der Judenstaat – Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage” (The Jewish State: Proposal of a modern solution for the Jewish question), was first published in 1896, and was to become the manifesto of the Zionist movement. Shortly afterwards, Herzl travelled through Palestine. It was a trip that fuelled his fantasy. In his utopian novel “The Old New Land”, he develops the notion of a “Jewish state of the future”, with spacious public squares and hedged-in palm gardens at its centre – lined by palace-like buildings featuring arcades and housing the offices of international companies and banks.

Broad avenues that are accessible for road traffic lead to the square from all sides. This commune of the future has state-of-the-art infrastructure with electric street lighting, a telephone network and a suspension railway. However, the character in the novel, the architect Steineck, does not set out to create a new city in the desert sand. Rather, he realises Herzl’s vision of already existing settlements, such as the Mediterranean community of Haifa and the time-honoured Jerusalem. And that is precisely where European master builders who could very well have been Wilhelm Stiassny’s grandchildren in terms of age were drawn to at the start of the 20th century.

City of the future

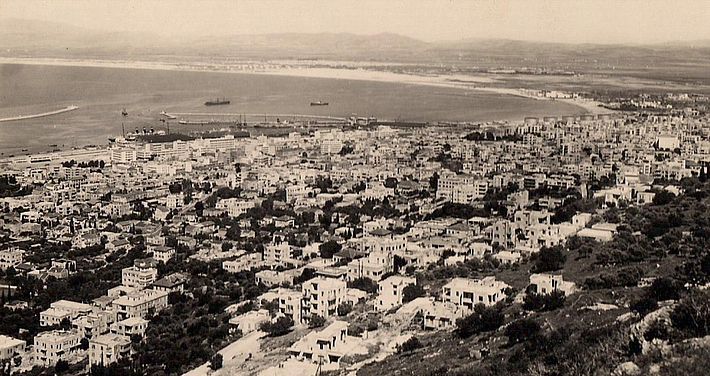

Particularly after British Foreign Minister Lord Balfour declared in November 1917 British support for the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine”, building work began. In Haifa, the modern district of Hadar Hacarmel emerged, which is today the preferred place for Israeli hipsters to live. At the same time, the architect Richard Kauffmann, a German emigrant, was at his drawing board designing the Rehavia district in Jerusalem. When the next generation of architects, in the person of Jewish doctor’s daughter Lotte Cohn from Berlin, applies to work for him, he askes her in a letter to bring along modern German building codes for “cities and garden cities”. He explicitly requests those from Essen, Hamburg and Cologne, and from Hellerau, which was built by “Zionist friend” Bruno Taut.

Jerusalem sees the emergence of a symmetrically arranged city district with gridded streets with no clear boundary to the Talbieh district with its mixed inhabitants and the chiefly Arab Katamon district. The garden city came to be fondly characterised as the “Grunewald of the Orient”. The Israeli urban planner David Kroyanker later called Rehavia a “Prussian island in an Oriental sea”. The area, close to Zion Square and the Jewish market, is still inhabited mainly by Yekkes, the name used in Israel for German Jews.

European standards were successfully used to encourage Jewish people to come to live in the new residential quarters of Palestine. The Nazis had not yet risen to power in Germany. From 1933 onwards, many Jews enter the country not because of their Zionist views, but to escape persecution. These include prominent architects from Berlin and from the Bauhaus in Weimar. It is the birth of the modern and urban Tel Aviv.

[GHH 2017; translation: DK]