Modernistic Idyll in a Deteriorating City

Lafayette Park Detroit

The foundation stone for Lafayette Park was laid in Detroit on 22 November 1956. It was here that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Ludwig Hilberseimer turned their ideas of flowing space and a New City into reality. Today the former industrial metropolis is the iconic image of a shrinking city – and Lafayette Park is an island in the middle of the eroding city.

[Translate to English:] headline

Detroit’s urban decline has been compared with the aftermath of an atomic bomb that had been released over the centre of the city, except it is as if the devastation of its explosion would have taken place in slow motion over decades. The former industrial metropolis is now a devastated and bankrupt city: at the very centre there are great numbers of vacant lots and abandoned buildings, the local public transport system is ailing, and the monumental train station meanwhile stands alone, decaying amidst an inner-city wasteland.

But not all of Detroit is a dreary place. No. There is an enclave within all this misery. The area is called Lafayette Park, and it was designed by ex-Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Ludwig Hilberseimer, an urban planner who was Mies’ former colleague in Dessau. Alfred Caldwell, who, like Hilberseimer, had worked with Mies in the 1950s at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago, was responsible for the landscape design. In Lafayette Park, modernism – nowadays demonised by many critics and viewed as having failed – seems like a functioning idyll in the middle of a deteriorating city.

Beginning in 1956, the 31.7-hectare site was built directly alongside downtown Detroit by the project developer Herbert Greenwald, who had already worked with Mies to construct the Lake Shore Drive Apartments in Chicago. The plans by the modernist dream team of Mies, Hilberseimer and Caldwell were never fully realised – Greenwald died in 1959 in a plane crash and other project developers subsequently took over.

[Translate to English:] headline

By 1963, Mies had built two 22-storey high-rise towers with rental apartments on the site, as well as 186 one- and two-storey townhouses that were privately owned but cooperatively managed. In 2015, Lafayette Park was designated a National Historic Landmark, noted as being “one of the most fully realised and most successful urban renewal developments of the mid-twentieth century”. It is important to know that Lafayette Park was the result of wholesale urban redevelopment – a densely built slum district with a predominantly black population previously existed there.

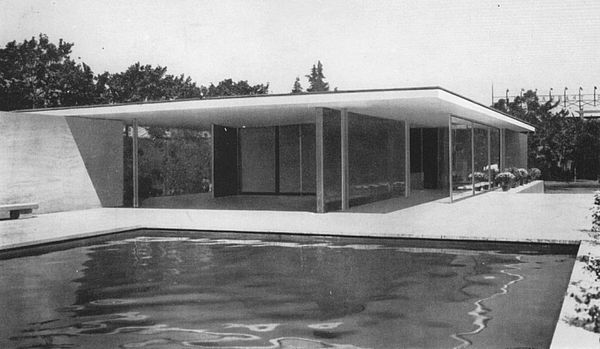

The Lafayette Park development is, by contrast, influenced by Mies’ concept of flowing space and incorporates much of Hilberseimer’s idea of a “New City”: the urban structure, for example, is completely free of through traffic and the built fabric is composed within a park landscape. Lafayette Park combines housing, recreation (park), education (school), and retail (shopping plaza); it even has its own swimming pool. To get to work, of course, residents must travel elsewhere, somewhere beyond the trees, highways and train tracks that surround the area and keep the rest of the city at a distance. Critics therefore speak of a “ghetto”, even though Lafayette Park is one of the few areas of Detroit that is ethnically mixed. Admittedly, however, those that live here are members of a well-to-do middle class that can afford it. Lafayette Park is an inner-city suburbia at the cost of isolation from the surrounding city.

[Translate to English:] headline

What might be a disadvantage in a functioning city becomes an advantage in the case of Lafayette Park. Amidst desolate surroundings, the housing complex functions, as it were, self-sufficiently. The residents of Lafayette Park therefore identify strongly with their neighbourhood. This is due in no small part to the development’s inner qualities. While the glass high-rise buildings were first and foremost initially the symbol of a fashionable lifestyle, prosperity and progress, interviews have shown that the residents now most value the neutrality of Mies’ buildings. The apartments in the Lafayette Towers and those in the townhouses and courtyard houses place few restrictions on their inhabitants. Mies’ high-rise buildings afford long-distance views of a city whose vertical expansion is mainly limited to only a few high-rise buildings in the nearby downtown area.

[Translate to English:] headline

From Mies’ low-rise townhouses, the views extend out into a park landscape because individually designed yards, as seen everywhere else in the city, are not found here. Mies defines the aesthetic, also through the lack of other influences – except for lawns, trees and solitary hedges. Even the cars are hidden in sunken parking lots that remove them from view. Lafayette Park thus represents the pure aesthetics of planning – making it the exact opposite of the participatory planning models which are currently in fashion. And that is exactly what the residents seem to appreciate. At the same time, however, Lafayette Park is also the alternative to a chaotic, apostrophised city, which Hilberseimer wanted to transform into the “New City” by means of rational planning. Such planned cities, too, are commonly regarded today as anti-urban.

What has emerged in Lafayette Park is a kind of suburban idyll, which at least offers the image of a “harmonious relationship between people, nature and technology” as conceived by Hilberseimer. Admittedly with a dependence on cars, without which no one can leave this island of the blessed, due to the lack of local public transport.

Text: Ronald Berg

- Special thanks to Christian Unverzagt, James Haefner, and Jamie Schafer for providing us the photos published here.