“Jeanneret” made in India

Modernity as a Global Network

The so-called “Jeanneret Furniture” of the north indian city Chandigarh is directly associated with Le Corbusier and the European 20th century modernists. But the core expressive structural logic of the furniture was derived almost entirely from the local, traditional ways of working wood by hand. Such phenomena reveal modernism to be a multi-lateral, international project.

bauhaus now

This article is from the first issue of the magazine „bauhaus now”.

Dr Vikrāmaditya Prakāsh (Seattle) is director of the Chandigarh Urban Labs and works on Modern, Postcolonialism and Urban Theory.

Amie Siegel (New York) is an US-American artist. Her films, video installations, and photographs are internationally renowned.

[Translate to English:] headline

Recently liberated from colonial rule, Nehruvian India sought to exploit the contradiction between the modernist and colonial projects to invent for themselves a new idenity as the world’s political avant-garde, to make India more modern than the modern West, with more advanced and more progressive political institutions and agendas than even those of the Western nations on which they were based. Chandigarh, as both an instrument and symbol of its aspiration, was certainly central to this script.

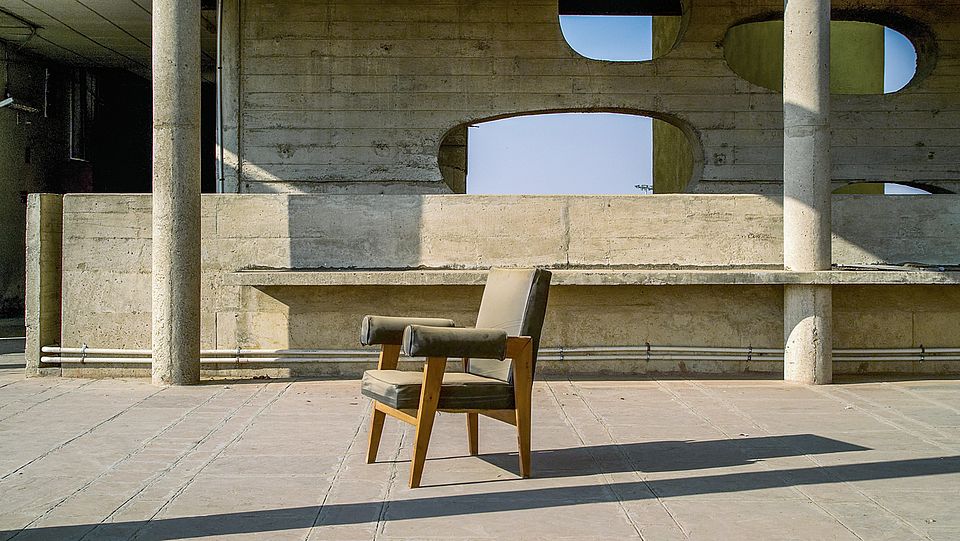

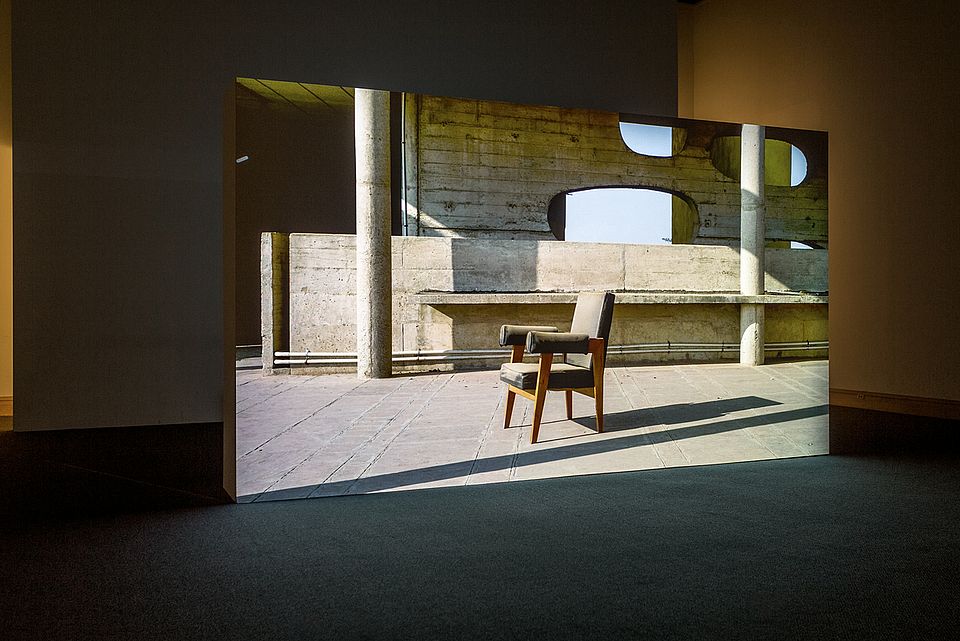

50 years on, as both the Nehruvian project and the modernist legacy, are facing erasure, what epistemic frame is best suited for the preservation of Chandigarh's modernist architecture? The question is: how is modernism’s provenance as an international political project to be parsed? How do we distinguish between the modernist architectural object and its political aspirations? According to the New York Times of 19 March 2008, Chandigarh is a city “that sat on its treasures and did not see them.” The “treasures” it refers to are the thousands of chairs and other pieces of wooden furniture that were designed by the Chandigarh Capital Project Team in the 1950s and 1960s to furnish the structures that they were furiously building at that time. Like the architecture, 50 years later, this furniture, handmade by local furniture stores and craftsmen, is rundown and dilapidated. For some time now it has been replaced by new furniture, woefully purchased from manufacturers’ catalogs, usually at significant cost, but of no particularly significant design merit given the Chandigarh tradition of modernism.

[Translate to English:] headline

The New York Times critique, however, refers not to the poor taste of the new furniture but to the lack of preservation of the old. As per the antiquated bureaucratic logics of the government of India, old discarded furniture must be kept in state-owned warehouses, where it is piled up like trash, until after some time it is sold via auction to the highest bidder. Usually this old furniture is bought by the recycling entrepreneurs of the informal sector, who then sell what they have bought in bulk at a small profit to the poor, who use it either as furniture or, more often, as firewood.

The ethics of this recycling of a worn-out modernism are worth dwelling on, but this is the road not taken in the New York Times critique either. The genesis of this critique is a handful of French and American art collectors who have shown up at the state auctions, easily outbid the recyclers to buy the furniture for pennies nies a piece, and after completely refurbishing it in their warehouses back in Europe, have profitably re-sold each item at auctions for upwards of $20,000. “There was nothing illegal about the purchase by foreign dealers of the furniture, much of which was being thrown out or sold by the city’s administration. But very belatedly, heritage experts in Chandigarh are lamenting the loss of a vital part of the city’s original design”, as the New York Times article noted.

The crime here, if the media hype that followed is to be believed, is committed by the government of India, which, as the headlines of the New York Times article declaimed, sat on its treasures and did not see them. The article bemoans the continued lack of recognition of the value of this furniture, and joins the clarion call for better preservation of the “treasures” of Chandigarh, entrusted to the Indian nation-state by its European designers, now under threat by the latest fashions of the global marketplace. Meanwhile, the outfall of this chair affair has been that the Chandigarh administration has put a ban on the sale of all Chandigarh furniture. Consequently, the trash heaps are rising higher (and are now guarded by security forces), the informal sector recyclers have lost a good source of daily revenue, and there is a flourishing blackmarket for furniture.

In 2009, the Chandigarh Urban Lab inventoried the publically accessible modernist furniture. Our focus was not on conducting an inventory of the total financial “value” of the furniture, or the total numbers of the furniture that exist, but on their design logics, an effort to document and hopefully better understand the essence of their form and their made-in-India, and rescued, “story”. We found very quickly, that the furniture was, of course, not all designed by Pierre Jeanneret (the cousin of Le Corbusier), despite being celebrated as “Jeanneret Furniture”. The furniture is directly associated with Le Corbusier and the European 20th century modernists, which is crucial for its provenance. And so we find that at least A. R. Prabhawalkar, U. E. Chowdhury, B. P. Mathur and Aditya Prakash were designing a lot of the furniture that was made in Chandigarh at the time.

The question of the logics of the design of the Chandigarh furniture, their derivation and influences, remain. Ostensibly, the core design logics of the furniture are ergonomic and material, i.e. designed to accommodate the ideal body in a defined state, structured by the core qualities of the material, i.e. wood. The modernist proclivity for universal ergonomics is well known.But the Chandigarh furniture also has its own local provenance. Interviewing some of the architects who had worked on the furniture and some of the woodshops that had built it, we learnt that the furniture was designed to accommodate local joinery and woodworking techniques. The furniture was handmade because it was cheaper to build it that way. There is considerable innovation in the Chandigarh furniture, but that innovation lies in building on the local joinery techniques and material strengths of the wood, placing faith in hands of the scores of local woodworkers who built it.

[Translate to English:] headline

In time, as more and more of the furniture was designed, the more “Indian” it began to look. Towards the end of his life, Jeanneret famously lived amongst one-off items of furniture that played with a diverse array of local materials and joinery, produced more cheaply than the cheapest furniture of yore. A perspective that focuses solely on the provenance of form retraces the furniture’s shared provenance back to the West, in the design agencies of Le Corbusier, Jeanneret, Perriand, and Prabhawalkar, Prakash and Mathur. And it pits it against a perspective that focuses on the material conditions of production, which points in the direction of the hands of the unnamed, subaltern craftsmen. This is not a double bind, or a contradiction that is difficult to resolve. It is a question of politics, of the politics of modernity and of the contemporary evaluations of its objects.If we see the modernism of the furniture primarily in the modernist-looking forms of the furniture, then its sources are singular and Eurocentric, and its commerce in the (editor’s note: so called) third world yet another instance of the neo-colonial exploitation of modernism’s global hegemonic aspirations. This is the normative, postmodern view of architectural modernism, its aspirations and ultimate identity.

[Translate to English:] Headline

But there is also another reading that determines the aesthetics of modernity as fundamentally linked to the actual conditions of production, that understands its aesthetics not simply as referring to timeless designs, but to an aesthetic project that is essentially tied to its place of production. This is what is occasionally characterized as the global, cosmopolitan, or translocal perspective. Modernity itself can thus also be described as a global network of translocal production.

This article was originally published in the first issue of the “bauhaus now” magazine.

[VP 2017; translation: Sylvia Zirden]