Focus on the Bauhaus educational principles

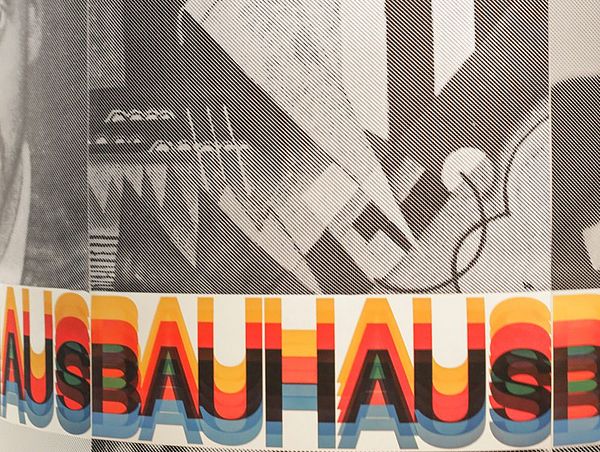

bauhaus imaginista

bauhaus imaginista in Japan: With Yuko Ikeda, curator of the exhibition, and Dr. Helena Čapková (Curatorial Research) we talked about the universal educational principle of the Bauhaus and its importance for Japan and India.

The exhibition “bauhaus imaginista – Corresponding with” in Kyoto traces the connection between the bauhaus, India and Japan — how can these relations be summarized?

Yuko Ikeda: The connection between the Bauhaus, India and Japan suggested in this exhibition, traces the universal value of the educational principles developed at the Bauhaus. Due to the universalist perspective of these principles – not only ideally stated in the Bauhaus Manifesto but also appearing in the practical curriculum and theory – they carried the capacity to be applied to art and design education in Japan and India and suited the local social and cultural demands.

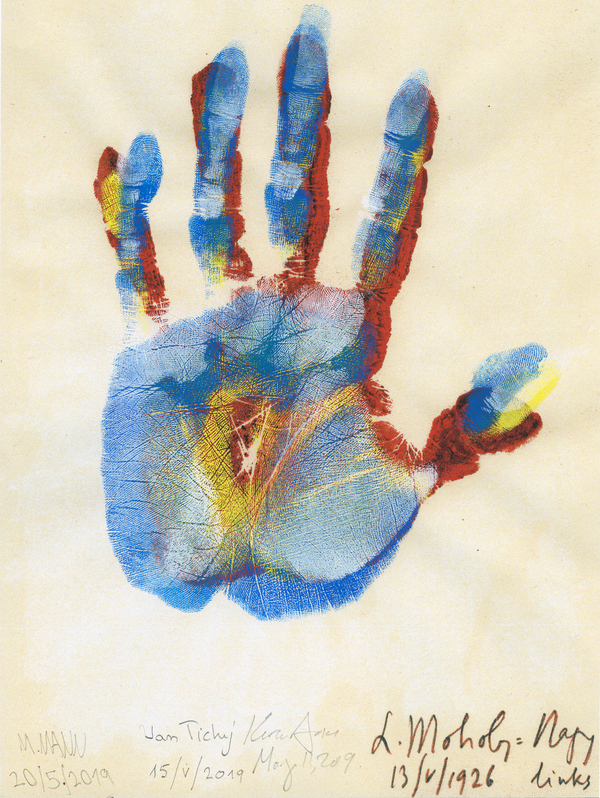

Helena Čapková: The exhibition concept brings the educational principles of the Bauhaus to the foreground and uses them as keywords to show correspondences among the three schools in different locations: Bauhaus in Germany, Kala Bhavan in India and the School of New Architecture and Design in Japan. The art works, archival materials, photographs, and educational tools highlight the parallels, similarities, but also differences in the ways progressive design education was interpreted and appropriated in India and in Japan.

What does participating in the bauhaus imaginista project mean for the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto? What kind of visitors do you expect?

Yuko Ikeda: The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto is one of the leading museums in Japan focusing on design movements since its foundation. We had several important design and architecture exhibitions, about Frank Lloyd Wright for instance, but also Bruno Taut, Johannes Itten, Hermann Muthesius and the German Werkbund. We also try to have hybrid exhibition concepts; trans-cultural, trans-art genre, trans-period. In this sense, the exhibition project “bauhaus imaginista” is suitable to the museum’s concept.

Historically, Kyoto has been the most important Kunstindustriestadt in Japan. Many art and design schools are active here. Students and teachers of these schools are potential and expected visitors of this exhibition as well as all people interested in art and design.

The Japanese architect Renshichiro Kawakita brought together elements of the Bauhaus with diverse other influences. Among them the Modern Japanese movement or local craftsmanship. How can these influences be distilled into an exhibition today?

Yuko Ikeda: Since the Meiji Restauration in 1868, the reform movements of art and design education were introduced in Japan and its newly opened schools of art and design. Influence came from progressive educational methods at the South Kensington School in London, Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule and others. One of the main aims of these reforms was to support industrial development. The school authorities and the Japanese government tried to combine the influences from London, Vienna etcetera with Japanese traditional methods in art education and local handicrafts as well as industry.

It is in this historical context that Kawakita tried to develop a more universal Gestaltungslehre influenced by the Bauhaus, which was to develop a comprehensive view on art and design. This was especially interesting for people who wanted to contribute to the social development of Japan with artistic creativity, embracing its commercial possibilities, as well as art teachers who wanted to develop the creativity of children and saw it as an elemental social power. For these purposes, he organized the Research Institute of Life Construction (later School of New Architecture and Design) and published Kosei Kyoiku Taikei (Manual for Teaching through Construction). This is why we focus on these two issues in this exhibition.

You already mentioned Kawakita, who founded the Institute of Life Construction, a research institution of higher education. To what extent did the institute advocate the approach of Bauhaus thinking and continued it until today?

Yuko Ikeda: The important point is that Seikatsu Kosei Kenkyusho (Research Institut of Life Construction) founded in 1931 is NOT a school. This was an organization to promote the educational principle developed by Kawakita and his associates through exhibitions, lectures, workshops and so on. The institutional form developed through these activities was the School of New Architecture and Design opened in 1932. But this school was very small and private and can not be compared with art and design schools like the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Tokyo High School of Industry and Design and others. Kawakita’s education principle taught at his school extended through his publication rather than the school itself.

Helena Čapková: The Institute was a short lived, experimental environment that fostered research into how ideas of contemporary avantgardes abroad could be employed in Japan and in the process of shaping modern Japanese design. It was also a platform for promoting these ideas to larger audiences that produced publications, organized lectures and seminars. In 1932, the Institute transformed into a school, sometimes called Japanese Bauhaus, which was small in size, but educated some key proponents of modern Japanese design, such as textile and fashion designer, theorist and journalist Yoko Kuwasawa. Kuwasawa Design School (KDS), established in 1954 became a hub for bauhaus style education and it continues to inspire and educate top designers in Japan until today. However, KDS is only one example of how the bauhaus legacy has carried on to the present; some other architecture, art and design schools share this legacy as well.

Thank you very much for the interview!

[CG 2018]