Two Rooms, Kitchen, Avantgarde

The New Frankfurt

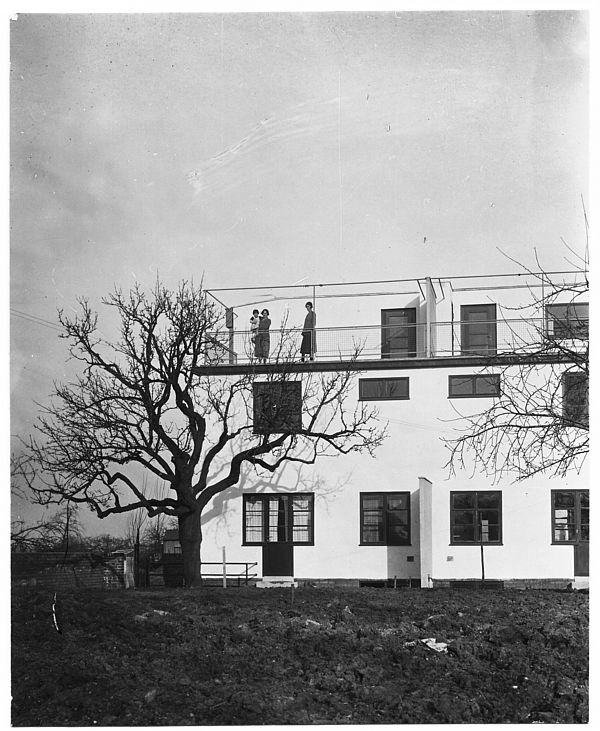

The Bauhaus in Hessen: Did something deserving this name exist in the Weimar Republic? The answer could be “Yes, but...”. This especially applies to Frankfurt am Main which attracted attention in parallel with the Bauhaus. The “New Frankfurt” was the second centre of departure next to Dessau from 1925 onwards. Not an aside of the Bauhaus, but a real star on its own and with its own energy.

Absatz 1 + Autorin

The project of the New Frankfurt inspired a whole metropolis with an atmosphere of departure towards modernity. It was managed by a city council which worked to transform the city into a “Big Frankfurt” under its lord mayor Ludwig Landmann. The programme included the design of the city, its green policy, the building of homes, the cultural programme and economic development.

Dorothea Deschermeier (Heidelberg) is a freelance architectural historian and curator. Together with Wolfgang Voigt, she has organized the exhibition "Neuer Mensch, neue Wohnung. Die Bauten des Neuen Frankfurt 1925-1933" for the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt/Main.

Absatz 2

Frankfurt became a centre of the avantgarde. What was decisive here was that theory immediately became transformed into practice. Within only a few years some 12.000 apartments and many public buildings like schools, swimming pools, market halls and industrial buildings were erected. The centre of this modernisation effort was the planning department headed by Ernst May. He assembled a team of young architects who were excited about modernity. Just to name some of the protagonists: Ferdinand Kramer worked on the typification of the designs, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky from Vienna designed the famous Frankfurt Kitchen, Mart Stam was invited to plan the Hellerhof Siedlung, Adolf Meyer left the office of the Bauhaus director in Dessau to construct industrial buildings in Frankfurt and direct the city’s construction consultancy. Walter Gropius also visited the city and planned the quarter Lindenbaum in 1929 at the invitation of Ernst May.

Absatz 3 – 4

The achievements of the New Frankfurt were presented in the monthly magazine of the same name whose modern graphics were designed by Hand Leistikow and later also by Willi Baumeister. The magazine was distributed internationally, had photo captions in three languages and some 135 subscribers in Japan. It may be difficult to imagine today that the influence of New Frankfurt was at times greater than that of the Bauhaus.

The most urgent task of the New Frankfurt was to alleviate the dramatic lack of apartments which was a problem in all major cities. The construction of new residential estates offered the opportunity to establish the concept of a new living culture on a broad foundation. Since 1900 the circles of “Life Reform” which were inspired by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche propagated the idea of a “New Human Being”. This notion was released from its elitist ivory tower to become an inspiration for mass architecture.

Absatz 5 – 6

The architects in the Frankfurt civil engineering office saw themselves as legitimate instructors to create the New Humans. The aim was to transform the inhabitants of the new estates by the layout, fittings (system furniture, Frankfurt Kitchen) and technology (electrification, radio) in their new flats. At times the ideal and reality did not necessarily meet. Kurt Schitters remarked resignedly but with humour: “It can of course become as in the Frankfurt estates where people arrive with their green fluff sofas. […] But we hope that the house will ennoble them” (1927).

An exhibition in the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt am Main entitled “New Human, New Housing. The Buildings of the New Frankfurt 1925-1933” (until 18 August) not only presents a selection of the most important buildings and estates but also examines the undoubtable discrepancy between desire and reality.

Absatz 7

The New Frankfurt has its place in architectural history, but only to a lesser extent among the public, and this is due to a number of factors. On the one hand, it was the life of Ernst May who went to the Soviet Union in 1930 to build estates. When his career there ended in 1933 he could not return to Germany which was then governed by the National Socialists. He went into exile in North Africa and developed a career as a coffee farmer and architect. During World War II he was a prisoner in a British internment camp for a number of years and therefore totally isolated. During these years Gropius in the USA developed the narrative of “his” Bauhaus successfully. In addition, the largely anonymised designs of the New Frankfurt architects who worked within an efficient and bureaucratic organisation did not match the idea of the architectural history of the 20th century which was oriented entirely towards the „masters“.

Absatz 8

If you walk through Frankfurt today, you find buildings from the brief period of the New Frankfurt in many locations. The estates are inhabited and the city buildings in use. Hardly any building was demolished over the years. The estates were changed by their inhabitants who reconstructed and enlarged their living space. Some of them are subject to preservation, but appropriate maintenance has been lacking for some time. The official documents on the UNESCO World Heritage status which was awarded to the Berlin estates of modernity in 2008 include the not very favourable comment on Frankfurt that its estates would have deserved the same due to their historical importance and effect, but their poor condition would not permit that. The city of Frankfurt is now considering its modern inheritance. It plans to convert some streets into a condition suitable for historic monuments so that they may be experienced as an architectural unit once again.

Absatz 9

The tight residential market and exploding land prices, which exist not only in Frankfurt, recall the dramatic situation of the lack of living quarters in the Weimar Republic after World War I. At the time, Frankfurt responded with a building programme for social flats and organised the CIAM Conference on “Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum” (The Flat for the Minimum Wage) in Frankfurt. Now the historical New Frankfurt is a driving force in architecture: last year the City of Frankfurt, the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) and the AGB Frankfurt Holding arranged the architectural competition “Living for all. The New Frankfurt 2018” for innovative and affordable housing whose contributions were on show at the DAM until 23 June. The four award winners – Duplex Architekten from Zurich, schneider + schumacher Architects from Vienna/Frankfurt am Main, NL Architects from Amsterdam/Studyo Architects form Cologne and Lacaton & Vassal from Paris will be able to realise their projects successively on a plot belonging to the city of Frankfurt. Ernst May would no doubt have liked it that the achievements, efficiency and innovative power of the historical New Frankfurt are honoured in this manner.

New Human, New Housing

Architecture of the New Frankfurt 1925-1933

23.03.2019 – 18.08.2019

Frankfurt am Main, Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM)

Schaumainkai 43

60596 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

[DD 2019; Translation SR]