Masters and weavers

On the role of women in the laboratory of modernism

In this Bauhaus centenary, one often gets the impression that this laboratory of modernism was a trailblazer for pretty much everything. Its combination of industry, art and craft, its teaching methods, publications, the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk... And last but not least, a holistic understanding of aesthetics, which many architects still value today as their personal guiding principle.

[Translate to English:] Text

Despite its short lifespan of less than 15 years, the Bauhaus remains a source of inspiration for countless current trends today. The Bauhaus #itsalldesign was the title of an exhibition on this at Vitra Design Museum in 2015.1 “From the city to the pen, everything that surrounds us is Bauhaus,” writes Patrick Schumacher of Zaha Hadid Architects in My Bauhaus. Mein Bauhaus.2 Yet despite all the praise, a counter-question might be justified: What is not Bauhaus these days? In other words: What should we do better than the Bauhaus? Where should we take distance from it?

This essay from Sandra Hofmeister is part of the book "Our Bauhaus Heritage". Ten international authors explore the question of whether and where Bauhaus has left its mark on contemporary architectural events. With contributions by e.g. Aaron Betsky, Zvi Efrat and Kenneth Frampton.

See publicationGender role reform

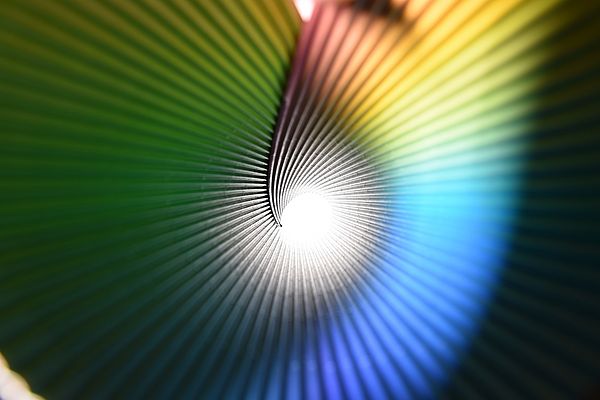

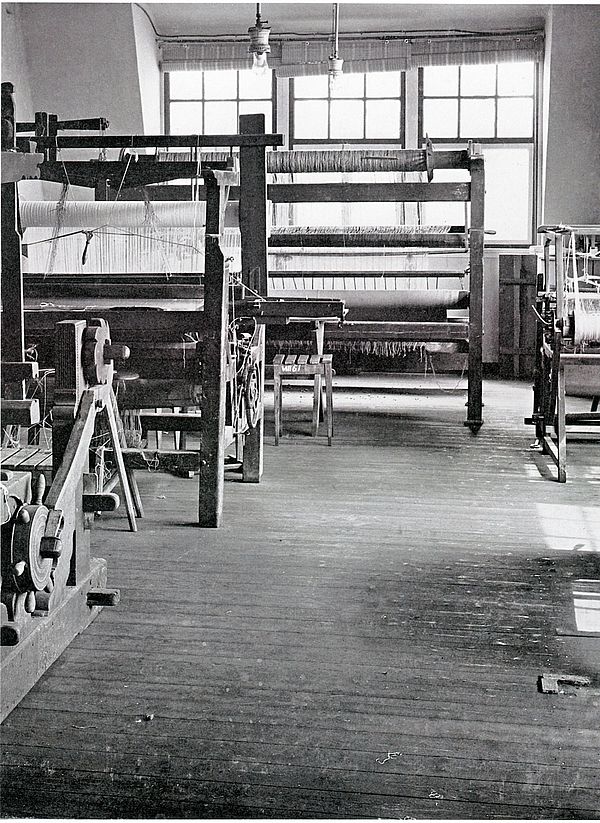

On 19 January 1919, women were permitted for the first time to vote in the election of the German National Assembly. A few months later, the Bauhaus founding director, Walter Gropius, noted in a speech at its opening in Weimar: “No difference between the beautiful and the strong sex. Absolute equality, but also absolutely equal duties.”3 The new human being who was to be formed at the Bauhaus could also be female – at the time, this was by no means a matter of course.4 For the 1919 summer semester, 79 men and 84 women were admitted to the art school. At first glance, this might be considered a success, and apparently linked to the institution’s idea of reform. Black-and-white photos of the time depict female Bauhaus students as self-confident design pioneers with cropped hair and sometimes even wearing trousers. But the image of this new type of woman that is often associated with the Bauhaus does not tell the whole story. Shortly after the school’s founding, the entirely male council of masters felt overwhelmed by so many women. In September 1920, Gropius called for a “sharp segregation” from the “over-represented female sex”.5 The otherwise free workshop choice was extremely restricted for female students, who from then on were sent to the weaving mill to study. The male domains remained closed off to the “fair sex”. Numerous workshop directors made it blatantly clear that women were undesired – be it in pottery, graphic printing, at the metal workshop or in mural painting. Oskar Schlemmer, who joined the Bauhaus in 1921, has been quoted as saying, “Where there is wool, there is also a woman who weaves, even if only to pass the time.”6

Women's careers at the Bauhaus

When it came to the role of women, this elite modernist school was not revolutionary and future-oriented, but old-fashioned and rather backward-looking. “The strategy of stealthy obstruction was effective – the masters did not dare to proceed openly,” notes Ursula Muscheler in her recent German-language book, Mutter, Muse und Frau Bauhaus. Die Frauen um Walter Gropius (Mother, Muse and Mrs. Bauhaus. The Women Around Walter Gropius).7 As an institution, the Bauhaus did not support women as such, but rather tried to commit them to a role that corresponded to the prevailing conservative image of women and housewives held by the master craftsmen. So it is all the more astonishing that some of its female students nevertheless made a career for themselves, thanks to the support of individual masters. Among them are Gunta Stölz and Anni Albers, who, despite the circumstances, turned the weaving mill at the Bauhaus into one of the most successful workshops. Under Mies van der Rohe, Lilly Reich headed the workshop for interior design. Marianne Brandt studied with Lázló Moholy-Nagy and, after his departure, took over the management of the metal workshop. Both women also worked as architects: one in Walter Gropius’s office, the other with Mies van der Rohe.

Pioneers of architecture

The dawn of modernism in Europe is rightly understood as the dawn of women who first conquered the field of architecture – from Charlotte Perriand to Margarethe Schütte-Lihotzky and Eileen Grey. At the Bauhaus, the pioneers were generally more tolerated than welcomed. 100 years after its foundation, it is time for an assessment that looks back on the Bauhaus from the present. When the American architect Robert Venturi received the Pritzker Prize in 1991, his longtime partner in life and work – Denise Scott Brown, with whom he co-founded Venturi Scott Brown Associates in 1964 – was left out. “Room at the Top. Sexism and the Star System” is the title of a lecture by Denise Scott Brown from 1973, published as a book in 1989,8 a sobering account of the institutional discrimination against women that she experienced during her career. To this day, women in architecture are often outsiders, and it is not self-evident that they will be taken as seriously as their male colleagues. Despite a petition, Denise Scott Brown was not retroactively awarded the Pritzker Prize alongside her husband. But the 87-year-old architect has never given up the fight for equality. In a recent interview, she offered a word of advice to young female architects and university graduates: Another thing is accepting that architecture trains you for many, many things and not necessarily in architecture. But if you can, try and do it on your own terms.

Now what?

These days, the architecture departments of most European universities have more female than male students. But there is no spirit of optimism to be felt. It remains difficult for women to establish themselves in the profession upon completing their studies and to gain recognition as architects. This applies not only to independent offices and to procurement and competition in general, but also to teaching staff at universities. Today, professorships in architecture faculties are still predominantly held by men. Compared to the situation at the Bauhaus, much has changed for the better with regard to women's rights, but the breakthrough has by no means been achieved. As in the past, the majority of university professors are male. But at least there are more women among the students. Universities, publishing houses, institutions, juries, building owners and personnel departments: all of them must ask critical and self-critical questions and take on the challenge of gender equality. It is for good reason that, for many, Denise Scott Brown is a star. But women are not yet equal in architecture. So let’s keep pushing forward.

[SH]

- [1] The exhibition was shown in Weil am Rhein, Bonn, Tel Aviv and Brussels. The catalogue was edited by Mateo Kries and Jolanthe Kugler

- [2] Sandra Hofmeister, ed., My Bauhaus. Mein Bauhaus. 100 Architects on the 100th Anniversary of a Myth. 100 Architekten zum 100. Geburtstag eines Mythos, Munich, 2018, p. 208.

- [3] Quoted in Ulrike Müller, Bauhaus-Frauen. Meisterinnen in Kunst, Handwerk und Design, Munich, 2009, p. 16.

- [4] At the time, only a few art schools in Europe admitted female students. This included the Grossherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule in Weimar – a predecessor institution of the Bauhaus – under director Henry van de Velde.

- [5] Walter Gropius, letter from 2 September 1920, quoted in Ulrike Müller, Bauhaus-Frauen. Meisterinnen in Kunst, Handwerk und Design, Munich, 2009, p. 89.

- [6] Ursula Muscheler, Mutter, Muse und Frau Bauhaus. Die Frauen um Walter Gropius, Berlin, 2018, p. 97.

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] Denise Scott Brown, “Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture”, in Ellen Perry Berkley and Matilda McQuaid, eds., Architecture: A Place for Women (Washington DC, 1989), pp. 237–246. Reprinted as “Sexism and the Star System in Architecture”, in Denise Scott Brown, Having Words, London, 2009, pp. 79–89.