Kitchen Dreams

New Living

The mother of the built-in kitchen, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, would have turned 120 in 2017. Reason enough to learn more about her Frankfurt kitchen and how it attained such renown.

[Translate to English:] headline

From today’s standpoint, given our contemporary modern kitchen islands with diverse smart functions and large dining tables where people gather for a convivial culinary experience, the Frankfurt kitchen of 1926 may not necessarily seem like a dream kitchen. But at the time, this kitchen was so innovative that a user manual stored above the stove was needed to introduce the lady of the house to the new amenities of her kitchen, which was meticulously designed in every detail.

In the 1920s, women were still “condemned, with only a few exceptions, (...) to run their households as in the days of their grandmothers.” [1] But the times had changed and many women, especially from middle-class circles, were now employed outside the home. That’s why Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky dealt at an early stage with the question of how proper home building could facilitate housework. She was inspired by the studies of American researcher Christine Frederick, whose book “The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management” had been translated into German in 1921.

[Translate to English:] headline

Ernst May, who knew Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s housing work in Vienna, brought her to Frankfurt am Main in 1926 to join his team at the municipal building department. There, she designed an efficient, space-saving kitchen for the housing estates of the “New Frankfurt” public housing programme, with simple, cost-effective, and above all hygienic furnishings. In the following years, these were installed in different variations and finishes in more than 10,000 apartments built under the New Frankfurt programme.

[Translate to English:] headline

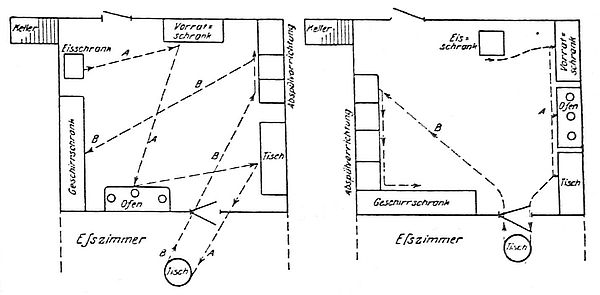

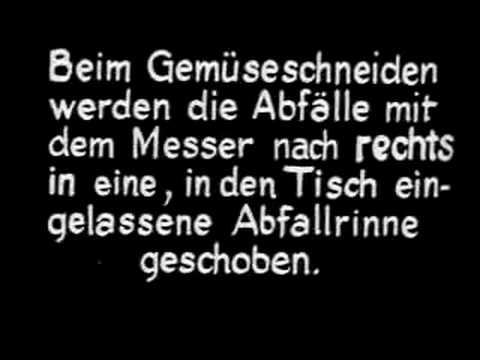

By optimising workflow, dispensing with an additional dining area in the kitchen, and efficiently planning the cabinets (shared side walls, no rear walls, and a continuous countertop work surface), the kitchen could be kept to a minimum size. The successive procedural steps were now organised in a sequence, so that it was no longer necessary to keep walking from one side of the kitchen to the other. Now the woman merely had to turn around, grasp the storage bin with the flour or the salt, and simply add a measured portion into the boiling saucepan in front of her. She could then conveniently place it on the so-called Kochkiste (cooking box) next to the stove or – even more refined – stored in this isolated Kochkiste in order to serve the ready cooked meal directly to the table in the evening, after all the work was done. That was how the architect thought about the ideal movement patterns in a kitchen.

[Translate to English:] headline

Datenschutzhinweis

Wenn Sie unsere YouTube-Videos abspielen, werden Informationen über Ihre Nutzung von YouTube an den Betreiber in den USA übertragen und unter Umständen gespeichert.

[Translate to English:] headline

How the Frankfurt kitchen was really used and how, after refrigerators and the like became prevalent, it was later modified or adapted by its users were investigated and documented in the 1980s by the architectural historian Jonas Geist and the cultural scientist Joachim Krausse in a wonderful series of films, in which Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and contemporary witnesses also have their say. “For many people it was not easy to imagine how to move around in there. It is, after all, so small; that was the main objection. Bear in mind: the houses in those days had kitchens-cum-living rooms, and you could move around easily in them. In the Frankfurt kitchen, everything was strictly arranged according to workflows. And people had to get used to that.” [2]

Lectures, publications, and exhibitions revealed the advantages of the new Frankfurt kitchen to the public and aroused attention abroad. In 1936 Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s kitchen design was included in Ernst Neufert’s “Bauentwurfslehre” (Architects’ Data) and in this standard work, spread throughout the world. As the forerunner of today’s built-in kitchen, it pointed the way with a unified design and sequentially coordinated functions – even though its elements could neither be combined at will nor adapted to different kitchens, as is commonly done today.

[Translate to English:] headline

The question remains: how would Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky conceive and optimise a kitchen according to today’s needs, in light of delivery services, convenience foods, Thermomix devices and other sundry kitchen appliances? It would undoubtedly not be a laboratory for work, which is how she had once described her kitchen. Just recently, Gerhard Matzig observed that while the kitchens of today are getting increasingly bigger, they are used less and less for cooking. [3] We make reference here with a wink to his sharp-tongued scrutiny of today’s dream kitchens.

Further links

[NO 2017]

- [1] Grete Lihotzky, “Rationalisierung im Haushalt,” Das neue Frankfurt, No. 5 (1926–27), pp. 120–23.

- [2] Interview with Ludwig Rössinger on 30 Sept. 1982, 1st instalment of the television film series “The New Frankfurt,” 3 documentary films by J. Geist and J. Krause, WDR, Cologne 1985 – quoted in: Die Frankfurter Küche: Eine museale Gebrauchsanweisung. Edited by Renate Flagmeier and Fabian Ludovico, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin 2012, p. 26

- [3] Gerhard Matzig „Hells Kitchen“ in: Süddeutsche Zeitung from 22. Sept. 2016