Crazy about Pictures

Hardly any discipline added to the regular teaching curriculum at a later stage, was as present at the Bauhaus as photography. John Grimes, professor emeritus of the Institute of Design, the New Bauhaus’ follow-on institution, and expert for the development of computer-supported digital imaging, gives an overview of 100 years of enthusiasm for imaging – from Dessau to Chicago, from the darkroom to the Cloud.

[Translate to English:] Absatz 1 - 3

The Bauhaus was not an art school, but it provided a very useful education for artists. The combination of art methods and insights with new technologies developed by engineering in the creation of a new set of artifacts for daily life combined with aspirations for social change beyond technical or commercial success, let the Bauhaus move forward in pursuit of a new role for art in a hoped for just and democratic society.

New technology in the time of the Bauhaus didn’t really mean “new.” Electric street lights had been selectively deployed decades before, but it wasn’t until the 1920s that Berlin’s households were electrified, enabling consumer level electric lamps and appliances. Likewise, it was in this time that industrial plywood, tubular steel, sound recording/reproduction, radio, movies, and offset lithography became practical and generally available.

Photography wasn’t new either, but safety film and small cameras, especially the Leica, made photography accessible to a much larger user base. Unlike drawing it did not require years of training and practice. Of any medium it lost the least on the printed page. A five-foot-wide color painting and a five-inch-wide black and white photograph became equivalent when reproduced five inches wide by grayscale black halftone. Every image became a photograph, and the original scale was invisible to the viewer. The image was separated from the object. Photography must have been invented for the Bauhaus.

Varieties of Photographic Seeing

Unconsciously, at least in terms of curriculum, photography was in every Bauhaus studio and at every event. All activities were documented, most thoroughly by Lux Feininger, but also by other students and masters, giving the Bauhaus a visual history unlike any school before. The most outspoken advocate of photography among the faculty was László Moholy-Nagy who taught from 1923 to 1928. His analysis of photography and its role in art and design were influential throughout his tenure. Moholy-Nagy laid out the case for photography in an evolving polemic first circulated in about 1925, and its second edition was subsequently published as Painting, Photography, Film, Bauhaus Book No. 8, in 1927. There are a number of themes in his book but two are especially important.

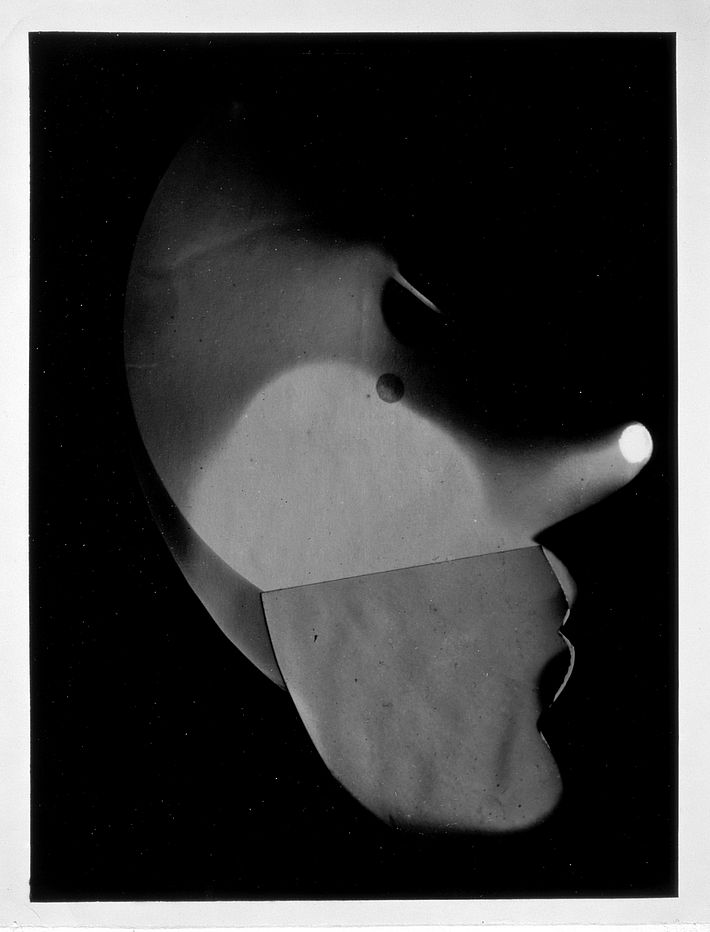

The first is the investigation of light as a new medium of expression. Light, in Moholy-Nagy’s view was the essence of photography. The book traces the progression of the photogram – painting with light, the light modulator (recording the forms created by light and shadow in the world) , moving light (light in kinetic sculpture), to public multimedia event (film, and multiple projections of film and modulated color light sources on scrims, fog, and clouds along with sound). Color was part of this but not technically practical until later, when Moholy-Nagy asserted that his New Vision proceeded from chiaroscuro (the photogram) to color, from color pigment to color light, and from color light to color light in motion.

Second is the assertion that a new basis for image making can be found in the examination of vernacular photography and commercial photographs published in the graphic magazines of the day – Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung, Münchner Illustrierte Presse, Survey Graphic, etc. From these sources and photographs by artists like Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy starts to build a map of new imaging using strategies non-existent or very rarely used in the know corpus of art.

All the elements are there in painting, photography film but unidentified by category: photograms, color light organs, negatives, light modulators, long exposures producing virtual volumes, very short exposures to stop movement, worm’s eye views, bird’s eye views, transparent superimposition, repetition with variation, X-rays, optical tricks and jokes. Later, in Telehor Vols. 1&2, he codified these as his Eight Varieties of Photographic Seeing. These were the methods that would allow users to explore the unique properties of the medium of expression.

Teaching photography

Photography was not formally taught at the Bauhaus until 1929, and then by Walter Peterhans whose aesthetic theories (and spectacularly beautiful still lifes) were quite different from what Moholy-Nagy had in mind. When Moholy-Nagy founded The New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937, he included photography in the foundation as the Light Workshop. It was first taught by Gyorgy Kepes, his countryman and collaborator, and the course of study was based on The Eight Varieties of Abstract Photographic Seeing.

The students of the New Bauhaus, like those of its predecessor, were educated to work in industry, but just as Bauhaus students continued to do easel painting outside of class, New Bauhaus students sought to apply their training to artistic pursuits. This was especially true in photography. After Moholy-Nagy’s death in 1946, the photography component of the program became a sort of school within a school headed most famously by Arthur Siegel, Harry Callahan, and Aaron Siskind. These teachers adopted Moholy-Nagy’s methods but had little interest in the broader design program. They were artists pursuing Camera Vision and supporting themselves by teaching.

Their advanced students in the graduate program, which started in 1951, followed the same path, enabled by the vast expansion of photographic education in the United States from 1960 to about 1985 and further supported by a large number of new magazines, galleries and museum departments dedicated to art photography. This proved to be an unsustainable model in the long run.

Video

Datenschutzhinweis

Wenn Sie unsere Vimeo-Videos abspielen, werden Informationen über Ihre Nutzung von Vimeo an den Betreiber in den USA übertragen und unter Umständen gespeichert.

About John Grimes

John Grimes is a professor emeritus at the IIT Institute of Design in Chicago, where he teaches courses in interactive media, software design, visualization of information, and imaging. He is an authority on the history and development of photography.

Competing for attention

The history of photography is more the history of photographic books than the production, sale, and collection of individual works. The book was the principal channel by which images reached their audience. Graduates of the New Bauhaus, renamed the Institute of Design in 1944, are vastly overrepresented relative to their numbers in publications of art photography.

Today the internet is a larger and arguably more important means of reaching the audience for visual works, and the problems of today do not center on the creation of individual images or the printed page but on how to control the flow of images, text, sound, and kinematics in the digital ocean of the World Wide Web. Further, this new arena includes user interaction, a different way of structuring the user experience altogether. As with all new technologies the internet does not eliminate what went before but rather redefines it in present day terms. What was thought of as a new art form is better considered as an art movement.

Art photographs in the age when print was dominant were the size and color (almost always grayscale) of the printed page. Later, they took the size and color tonalities of a color television. In the current environment photographs by artists have become the size of art to compete for attention on the gallery wall, and the relation to the printed page is broken. Print isn’t dead quite yet, and the medium of photography undertaken as unique mode of inquiry is still shown and collected.

One now finds photographic prints in the main galleries of a museum addressing the concerns of contemporary art and ignoring the exploration of the unique qualities of the medium of expression. Art photographs are also found in the museum’s Photography Department where camera vision dominates. They are not the same sort of photographs.

[JG 2019]