“Short Sentences That Refuse to Get Old”

Interview with Ada Karmi-Melamede

Ada Karmi-Melamede is one of the voices that can be heard on the audio app of the shortly reopened Liebling House in Tel Aviv. Her father Dov Karmi is the architect of the building. An inspirational conversation about freedom of thought, architecture and rituals of a creative family.

You are one of the voices that can be heard on the audio app of the Liebling House in Tel Aviv. Your father Dov Karmi designed the building, and many more both residential and public buildings such as the El Al building and the Cameri Theater. He was the first architect to receive the Israel Prize in architecture in 1957 and his works belong to the modernist Israeli heritage. How did all this start?

My father was of the generation of immigrants from Odessa that came to Palestine at the beginning of the 20th century. They came from the vast reservoir of hope and despair, created by the political and ideological upheavals of Eastern Europe. He came to Pales-tine in 1918, went to high school in Haifa, and later studied painting in Jerusalem and architecture in Belgium at Ghent University.

How did he get involved in the influential movements of the times?

Belgium then, un-like Germany, Holland and France, was the centre of Art Nouveau, less influenced by the modern movement. Students were aware of the dogmas and manifestos of the modern movement, but were likewise free to interpret and apply the concept of style with great flexibility.

Bild 2

And your father brought these ideas back home.

This freedom of thought was a charac-teristic feature of my father. It helped him search for a socially oriented functional ex-pression of architecture, which could be realized utilizing local materials and technology – a modern language that related to topography, climate, shade, water and vegetation.

This modern attitude found its expression in the Liebling House.

Yes. Liebling House is an apartment building in Tel Aviv built in 1936 to 1937. It has a clean platonic form with a flat roof that faces on to the street. Its façade is layered. A slot running through its en-tire width creates a deep shadow and is reminiscent of the ribbon window without glass.

Behind this façade, the inner face of the building, shaded and protected, is marked by doors and windows. This layering created a public scale in the front of the building and a private scale in the back with a space in between, which acted as a balcony, used by the entire family as an extension of the living-room.

The asymmetry of the front façade leads one's vision towards the side entry. Here, the area that connects the sidewalk to the entrance door is covered by a wooden pergola. A spatial sequence is created which terminates in a beautiful vertical foyer with indirect light that leads to the apartments.

Bild 3

What would you as his daughter say, is typical for your father’s work?

Layering was a theme that reappeared in many of my father's projects. It was a unique aspect, which was not typical to the modern movement. Most of my father's buildings are like short sentences that remain clear and refuse to get old. His buildings descended gently to the ground, responded to the site and had both a local and a universal character due to their human scale.

You yourself now belong to the most important contemporary architects in Israel. How did your father influence you?

My father has presence in my work despite the fact that I have never worked with him. He died when he was 57 years old while I was still in the school of architecture. His buildings feel they belong here in terms of their spatial and material expression, their structural logic and their tactility. This combination has guided my work from the beginning. I learnt from my father that the material of architec-ture is space, its logic is structure, its tactility resides in classical tradition, and that its mood is in light. Consequently, I often use indirect light, which softens the texture and colour of local materials.

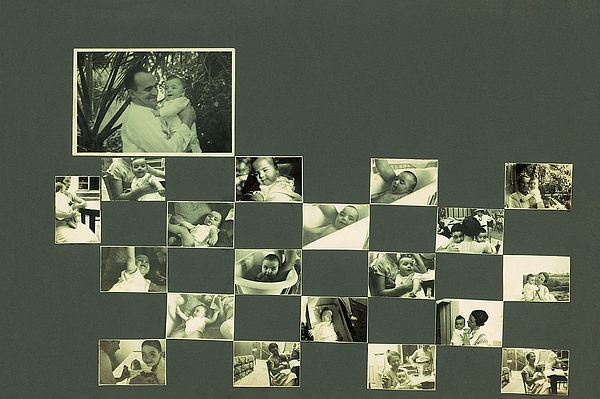

Bild 1

Were there certain creative rituals in your family?

Everyone in the family drew. And when we travelled I often saw my father sitting by himself drawing. He drew people, land-scapes and buildings with a thin ink pen. His freehand drawings and his architecture reveal great similarity because both are equally layered. My parents spoke four lan-guages. They were from this place and belonged here. Yet, they had an European back-ground which coloured their daily life and bestowed upon them a sense of proportion.

We lived in Tel Aviv in modern apartments, the last of which was designed by my father. My mother took great interest in interior design and was an important partner when it came to issues of taste. Our apartment was beautifully designed with crafted details and hand-made furniture. I learned from my father the importance of detailing and I feel that it's an inherent part of architecture, which reveals the nature of materials and the design pro-cess.

In 1967, you went to the US and only returned to Israel in 1986. Was this also an es-cape from your family? Did you want to step out of your father’s footsteps?

No. I went to the US in 1967, following my husband's career. I worked for Aldo Giuorgla and taught with him at Columbia University, School of Architecture for 15 years. And what should I say? My students were my best teachers.

Verborgen

Thank you for the interview!

[KK 2020]