Mysticism and Mazdaznan

How spiritual was the Bauhaus?

Modern, technically talented young people designing practical objects for an enlightened world: the fact that the Bauhaus was founded in Germany no doubt further strengthened its reputation, since both the Bauhaus and the country are internationally regarded as unemotional, rational and focused on reason. We take a look behind the glass façade and discover spirits in tubular steel chairs and true Bauhaus angels.

Text 1

A hundred years after its foundation, the Bauhaus is regarded not only as a paragon of functional design and empirically-based education. Its teachings, the unity of art and craftsmanship, and later of art and technology, made the Bauhaus a brand of enlightened Modern materialism. No wonder: until its politically enforced closure in 1933, the institution had long been regarded as the philosophical opposite of Nazi irrationality, with its fanatical yearning for political mythology and social pathos.

Written in 1932, a letter by a young Bauhaus protagonist shows how the opposite of National Socialist emphatics need not always lead to sober realism, even at the Bauhaus: “and then i heard hannes meyer. he reported on his work in Russia, i.e. he outlined his dreams, describing an ideal realm. it was cheap and very naïve. a populist spokesman. – i think of mies van der rohe. and i am annoyed that i have been held up by someone like him, such a fart.”[1] But it was not just the anger of this young student and the country’s new rulers in the face of widespread “Communist machinations” in the late Bauhaus that pushed the strict rationalism of its teachings towards a form of hagiography. Even its beginnings in Weimar (1919–1923) were deeply characterized by tendencies ranging from romantic to irrational.

Of ancient wisdoms and new religions

“There was certainly a means of recognizing the secret: namely revealing the secret. But a revealed secret is no longer a secret. The secret is destroyed. This way of coping with life actually destroys life.” To Lothar Schreyer, the director of the stage workshop from 1921 onwards, instead of enlightenment, transfiguration appears to have been the means of the day. Thus the author of the “Mondspiel” production, which flopped at the Bauhaus so spectacularly, presented a mixture of minimal dance[2] and cultic exercise[3]: “People now want something else: instead of destroying the secret by revealing it, they want to live a secretive life, which is the meaning of mysticism.”[4]

While the mystical Bauhaus Stage is almost forgotten today due to its realignment under Schleyer’s successor Oskar Schlemmer, another master of the early years is often named in the context of the “irrational Bauhaus”: Johannes Itten. This is because the inventor and first director of the famous foundation course was a self-professed follower of a new religious movement that extended Schreyer’s Christian spectrum to include Middle and Far Eastern influences. The movement, which had spread to Europe from the USA in the early 20th century, has the striking name Mazdaznan (pronounced “Masdasnân”) and was hardly older than most of the teachers at the Bauhaus.

A better future for everyone – as long as you’re white

Mazdaznan (which roughly means “master thought”) reflects the ambivalence of a time that simultaneously yearned for progress and reconnection. The aim of the “life teachings” founded by Otto Harnisch, who had emigrated from Germany, was the physical, mental and spiritual development humanity, based on a vegetarian diet, combined with breathing and physical exercises. “Thus, Mazdaznan offers no ideas or theories, but breathing lessons and exercises of all kinds (…)” that are calculated, “to support blood circulation, the nervous system and the glandular system, thereby allowing the brain’s intelligence to become more enhanced and effective.”[5] At first glance, it might be understandable that many Bauhaus protagonists, from Georg Muche to Walter Gropius, were interested in a way of life that philosophically consolidated the school’s educational ideals.

However, a look at a 1930 publication by the Leipzig Mazdaznan publishing house reveals that the movement, which focuses on world peace and nature conservation, also had its historical dark side. While the author of the book, the religion’s founder Otto Harnisch, places the universalist component of his message at the forefront (“Mazdaznan is (...) the joyful message of human salvation regardless of age, gender, class, occupation, faith or other temporary situation or condition”[6]), the book’s editor, Frieda Ammann, makes an addition that recognizes the spirit of the times: “Drawing from the source of eternal wisdom, our highly educated master presented all his valuable experiences and observations to us on a journey to Europe in 1929, which (…) should be passed on to all of white humanity …”[7]

The fact that Itten’s enthusiasm for Harnisch’s nutrition and health teachings also had racist implications is revealed in the manuscript of a speech by the Bauhaus teacher, which was published in 1994. Entitled “Contemporary art and the triple foundation of humanity”, he added the following note to his public lecture held at the Bauhaus on November 17, 1922: “White race recognized God in it/ Inspiration/ and gift of revelation/ collection of all senses/ complete thought./ Breathing teachings heart The true religion first among Aryans. But also true art.”[8] In view of the sincere interest of many Bauhaus protagonists in African art, it is not helpful that such Mazdaznan racism explicitly considered Jews to be of “white race”.

The Bauhaus as a séance and inspiration

The retrospectively developed narrative that the Bauhaus had realigned itself towards its original rationalism by 1923, following the departure of Johannes Itten and Lothar Schreyer, proves to be a mirage on closer inspection. “Even in it's focus on 'Art and Technology, a New Unity', the Bauhaus's engagement with the spiritual clearly persisted.”[9], as Elizabeth Otto writes in her book “Haunted Bauhaus”, which was published in 2019. Otto presents evidence of this not only in the continued “Lebensreform-related practices” by many Bauhaus protagonists, but also in archive finds such as a 1930 drawing of the “Seven Chakras” by Joost Schmidt, as well as Xanti Schawinsky’s “spirit photography” taken in the Dessau Bauhaus building shortly after moving into it – very much in the tradition of 19th-century spiritualism.

According to Otto’s description of the “Bauhaus spirits”, the effects of apparently “irrational activities” are not limited to such experiments, which are certainly interesting from an art-historical perspective. Instead, the open-minded stance towards spiritual themes appears to have been a fundamental characteristic of many Bauhaus protagonists, expressed as a binding quality of the Bauhaus founders rather than a side-effect. For instance Kandinsky, whose essay “On the spiritual element of art”[10] caused a sensation even before the outbreak of World War I, declared he filled his abstract paintings with forms that were derived from the unconscious and had more in common with feelings than logic. “It is worth noting that the work and pedagogy of one of the most influential Bauhaus masters is centered around anti rationality,” so Otto, “a strong contrast to stereotypes of the Bauhaus.” [11] Even an extensive horoscope commissioned in September 1926 for László Moholy-Nagy, who is often presented as the rationalist counterpart to his predecessor Itten, survives today, ascribing to the Bauhaus master, “the ability to produce his own creative work” combined with “a talent for teaching”.[12]

[Translate to English:] Bauhausbuddha

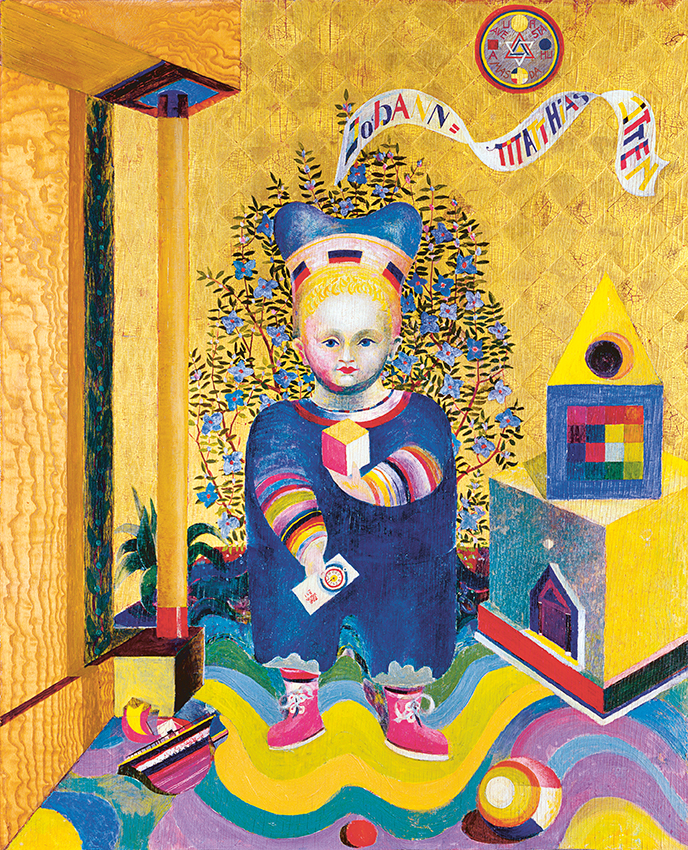

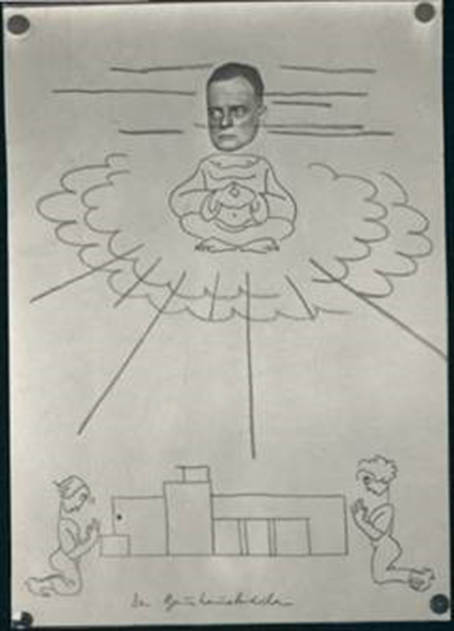

Paul Klee also belongs undoubtedly to the “religiously talented” Bauhaus protagonists. His famous work “Angelus Novus” was bought by Walter Benjamin in 1921, subsequently leading Benjamin to produce pieces on the Kabala, the study of angels and demonology. Even in the year of his suicide, the image by the Bauhaus master inspired him to his epochal description of the “Angel of History”: “His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”[13] Mythological creatures, deities and mysterious phenomena are constant themes of Klee’s paintings. It is no coincidence that Ernst Kállai declared him the “Bauhaus Buddha” in his legendary caricature.

Late objection

The most recent example of public criticism of the ambivalent character of some teachings at the Bauhaus came in 2012, when the city of Munich wanted to name a street after Johannes Itten. The otherwise highly regarded Bauhaus master was chastised for his racist Mazdaznan beliefs: following considerable protest in the press, the city’s building authority was forced to reverse its original decision. The street leading past the Domagk studios is now called Margarete-Schütte-Lihotzky-Strasse. This in turn caused a public outcry on the Internet: “Who can remember that name? What child can pronounce it? Who can spell it correctly? Who can read it on a sign while driving past?“[14]

Irrationality may not have been foreign to the Bauhaus, but it appears to have become even more widespread in the last 100 years.

- [1] Hans Keßler, die letzten zwei jahre des bauhauses / the last two years of the bauhaus, Berlin 2013, 10.

- [2] Joachim Noller, Klang/Bewegung. Musik und Tanz im modernen Gesamtkunstwerk, in: Constantin Floros/Friedric Geiger/Thomas Schäfer (Hrsg.): Komposition als Kommunikation. Zur Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt/Main 2000, 21.

- [3] Juan Allende-Blin, Gesamtkunstwerke – von Wagners Musikdramen zu Schreyers Bühnenrevolution, in: Hans Günther (Hrsg.), Gesamtkunstwerk. Zwischen Synästhesie und Mythos, Bielefeld 1994, 178 ff.

- [4] Lothar Schreyer, Deutsche Mystik, Berlin 1925, 7.

- [5] Dr. O. Z. A. Hanish, „Mazdaznan“ – Der Ruf an die Welt. Die frohe Botschaft der Errettung des Menschen, Leipzig 1930, 11.

- [6] Ibid, 9.

- [7] Ibid, 5.

- [8] Rolf Bothe/Peter Hahn/Hans Christoph von Tavel (Hg.), Das frühe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten, Ostfildern-Ruit 1994, 446f.

- [9] Elizabeth Otto, Haunted Bauhaus. Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics, Cambridge 2019, 46.

- [10] Here is Kandinsky's complete work as PDF.

- [11] Elizabeth Otto, Haunted Bauhaus. Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics, Cambridge 2019, 42.

- [12] Theo Spengler, Horocope from Mr. and Mrs. Moholy-Nagy, Sept. 1, 1926, 17. Estate of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor.

- [13] Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, herausgegeben von Rolf Tiedemann und Hermann Schweppenhäuser (werkausgabe edition suhrkamp), Frankfurt/Main 1980, Band I.2, 697.

- [14] Text of an online petition started in 2014.

[NF 2019]