Health at the Bauhaus

Spot on

The promotion and protection of health were important themes at the Bauhaus. As such, breathing and concentration exercises, and even works of art, were considered beneficial.

[Translate to English:] headline

Much like today’s ever-present “burnout”, in the 1920s “neurasthenia” was seen as the malady of the era. At the Bauhaus, the responses to this aggressive nervous condition affecting the emotionally imbalanced were manifold: health was a major theme which was closely integrated in the lessons and the creative work. It was assumed that only the balanced, healthy individual would be able to reach the heights of creative achievement.

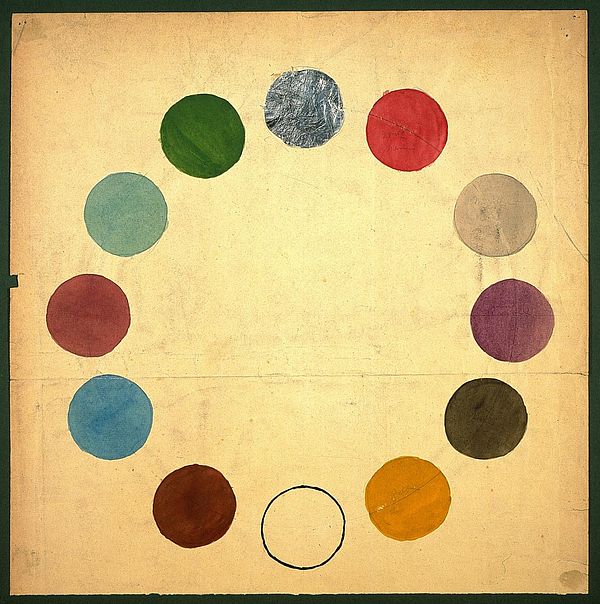

From 1920 to 1923 the “Theory of harmony” devised by the music teacher Gertrud Grunow formed a cornerstone of the Bauhaus curriculum. In her work with her students she endeavoured to stabilise body, mind and spirit through sound, colour and movement. Grunow developed a twelve-tone colour circle that was approached and sensed with the eyes closed. By tapping into colours on a spiritual level, the Bauhauslers would let go and recover a natural equilibrium, the aim being to offset organic and spiritual irregularities, inflexibilities and imbalances.

[Translate to English:] headline

Johannes Itten established dietary rules that he derived from the Mazdaznan doctrine. Meat, alcohol, tobacco and other luxury goods were taboo, while a porridge made from wheat, oats and barley was savoured. These, much like today’s organic foods and detoxification cures, promised to purify the body. He also integrated callisthenics and breathing exercises in his preliminary course, designed to school the capacity for experience and expression, rather than strengthen the musculature.

As with Grunow, the intention was to ease both body and spirit in order to release persistent tensions. In morning sessions, the students first expended their energies in gymnastic exercises that included spatial movements such as stroking, pulling, pushing, striking, touching, setting, grasping, playing and skipping. These were followed by calm breathing and concentration exercises similar to yoga, which served to create a sense of inner harmony.

[Translate to English:] headline

The question of health governed more than just the work at the Bauhaus. Beneficial effects were also expected from the works of art. Paul Klee mused on the question of how the observer might glean a similar effect from his paintings as they would from a temperate Mediterranean health resort. He set his brilliant and vibrant colour compositions against the backdrop of a grey, sunlight-deprived Dessau. He regarded his art as a “villegiatura”, a residence in the country for a (summer) holiday, which brings change and fortifies the spirit.

[Translate to English:] headline

Above and beyond all these things was the desire to return to a natural way of living, a natural rhythm, in order to counter the pains of an advanced, yet apprehensive society. At the same time, new ways of working and effective forms of regeneration were sought – a search that continues to characterise our present-day lives. Apparently aware that the progress of society was unstoppable, then as now humankind was to be armed against the challenges of a meritocracy and improve productivity and performance by means of a healthy way of living that preserved youthfulness. Spending time in the great outdoors as well as in the new bright and airy architecture which was conducive to good health was just as relevant as a good diet, physical activity and the ongoing harmonisation of body and spirit.

[LB 2017; Translation: RW]