Education Between Artificial and Artistic Intelligence

Roland Benedikter on challenges to pedagogy of the 21st century

The Bauhauslers’ vision of mechanization and machines for living in seems within our grasp in the age of artificial intelligence and smart cities. The growing influence exercised on politics and education by “transhumanists”—who speak out in favor of overcoming what it has previously meant to be human by means of a convergence of technology and humanity—confronts us with the other face of technological optimism.

About Roland

Roland Benedikter (Wrocław) is co-director of the Center for Advanced Studies at Eurac Research in Bolzano, affiliate scholar at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (IEET) in Hartford and a full member of the Club of Rome.

[Translate to English:] headline

One defining phenomenon of our time is that artificial and artistic intelligence seem to be becoming more and more opposed to one another. It takes less and less time for the examples to pile up. In October 2017, Saudi Arabia, a country recognized by the UN, granted citizenship to the robot “Sophia,” created by Hanson Robotics and supposedly equipped with artificial intelligence. This set a global precedent on the path to a “transhuman” society that is on its way to not just recognizing artificial intelligence’s human and personal rights, but—with them—indirectly recognizing it’s active and passive voting rights, as well. The first Cyborg Olympics, organized by the ETH Zurich in October 2016 and held at Swiss Arena in Kloten, and the first recognition of an artificial-intelligence robot (made by the Chinese company Iflytech) as a resident physician, after it passed China’s relevant state examination, also reveal—with an increasingly powerful signal strength in the public imagination of the West, as well—the ever-expanding use of AI robots, which support the trend towards replacing people in social-design contexts.

Algorithms are (still) not the better designers

Roland Benedikter

[Translate to English:] text

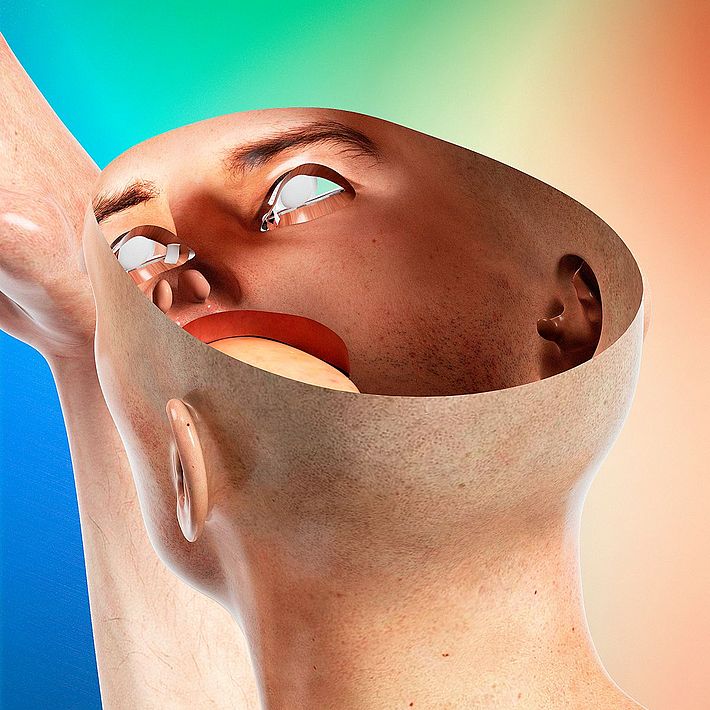

However, to counter the visions of those who wish to progressively make artificial intelligence the formative standard of our future, it is time for us to occupy ourselves with the irreplaceable qualities of a society-shaping personality. Its outstanding capabilities are individuality, human warmth, and the capacity to transform and change. The potential of facts to inhere within feelings, the personal uniting of object and subject in a kind of inward gaze and the capacity for intuition—in which the individual and the universal merge in the personal—are elements that artificial intelligence will presumably continue to lack in the future. There is also the human measure. Until now, this has been decisive not just in the areas of architecture and design, but always also as the “final” criterion for politics as a historical process of meaning. Precisely in the increasingly common “deeply ambivalent” issues of the future, artificial intelligence will not be able to provide any adequate findings in these fields.

Therefore, with regard to the construction of a new pedagogy, we are standing at a threshold similar to that faced by the historical Bauhaus: in the coming years, the field of education and schooling will have to increasingly take into ac- count artificial intelligence’s penetration of the spheres of social-artistic intelligence, and it will have to make a far more extensive investment in terms of preparation, program and time. If this field is to seek a humane society for everyone and preserve a social sculpture of people instead of a social machine of artificial intelligence and its social engineers, then it will have to explore new educational paths that place the personality, the human self, more emphatically at their center than has previously been the case. At the heart of its efforts, education must ask the question: what distinguishes the “self” from artificial intelligence? What links people and technology and what separates them?

Putting the fox in charge of the henhouse

In this context, the field of education will have to take into account ideas and approaches like those that had already been decisively incorporated into the Bauhaus and culminated in the notion that the self, precisely in its subjective—objective aptitude, is a self-perceiving interface: “Everything is, which is the case.” This raises both the question of the witness and that of responsibility. It applies to the priorities that have to lie with humanity and its coming to terms with itself—and it has less to do with individual practical or technical-cognitive abilities that can be learned by building upon this foundation.

The German and the European educational field will have to found its own interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary institutes for the future of humanity, because only a more comprehensive perspective can contribute to preparing for artificial intelligence’s potential awakening to self-referentiality, just as it is now powerfully pressing into the heart of civilization’s potential and its social and political decision-making processes. By contrast, specialized institutions like those still favored in German-speaking countries will be unable to substantially contribute to shaping the human—artificial intelligence interface, because they have to ignore too many social and design dimensions that will be relevant in the future. Is it possible, for example, to purely cybernetically control and overcome a major contemporary social issue like growing inequality, or will the future also require—possibly even more so, as interconnections and complexities increase— humane-empathic (in its narrower sense) and social-artistic components? Can inequality as an experience, challenge, and reality really even be understood by a non-human?

If we summarize the developments described here, a two-edged trend becomes apparent. At the present moment, no one would vote for politicians being replaced through artificial intelligence—particularly not in open societies that thrive on participatory and discursive processes, which are fundamentally foreign to the character of artificial intelligence. However, the scope and argumentation, as well as the breadth and intensity of the debate throughout the entire Western world, reveal the great depth of the crisis of democracy in its present form and of its political representatives. A substantial role in the destabilization of its core processes has also been played by new technologies, such as the new social media and the “fake news” disseminated through them. Now, of all things, it is the cutting-edge technology of the years to come, artificial intelligence, that is supposed to set matters straight—technology that is already substantially integrated within ambivalent mechanisms of information production and distribution today. Will the fox be put in charge of the henhouse?

No end for the human

Politics will have to make a great effort to resist artificial intelligence’s storming of the core areas of society’s formation and the educational field that makes it possible. Those who, like the Bauhaus, ask about the future of teaching and education today will come to a decisive point where they have to ask about the future of the interface between artificial intelligence, politics, and personality. Artificial intelligence, politics, and education will become more strongly inter- connected in the years to come than ever before. The challenges presented to the educational sys- tem will inevitably revolve around the essence of the human—particularly with regard to the question of how the fallibility, genius, and humanity of individual people differ from the formative power of the machine.

To a large extent, the discussion of and response to this question will determine the humanity of our future—and this cannot be realized without innovative educational approaches. If we thus ask ourselves, on the Bauhaus’s 100th birthday, which challenges face the pedagogy of the 21st century, the answer is: rediscovering and defending the human personality in comprehensive design processes, including politics—in order to keep politics, understood as a process encompassing all society, human. It is clear: algorithms are (still) not the better designers. But their defining characteristic is that they develop quickly, indeed, in many respects they are becoming exponentially more capable of complexity.

Headline

In this era of the sup- posed “end of the human,” this could—in the foreseeable future—just as easily contribute to the end of politics in its present form as it could present a challenge for a new politics. This new politics may even have already begun today with artificial intelligence’s rise to become the universal societal factor behind the scenes. It will play out at the interface between artificial intelligence and artistic intelligence, and it will thus continue shifting the existing self-concept of the political and social.

This article was originally published in the third issue of the “bauhaus now” magazine.

[RB 2018, translation: TK]