Bauhaus Weimar

1919–1925

In Weimar the Bauhaus was already a magnet for the European avant-garde because it was cosmopolitan in spirit and open to international artistic diversity.

Headline

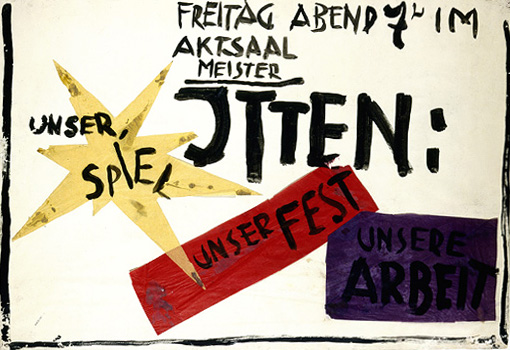

On 1st of April 1919, the cornerstone was laid for the school of design and architecture. Walter Gropius became the director of the former Grand-Ducal Saxon College of Fine Arts Art School [Grossherzoglich Sächsische Hochschule für bildende Kunst] in Weimar. He united it formally with the College of Applied Art which had been dissolved, and named the resulting institution the State Bauhaus in Weimar [Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar]. The school represented the spirit of awakening that was also dominant in the current politics, personified by the national assembly convening in Weimar at the time to pen the constitution of 1919. The high calibre artists Gropius appointed as masters at the Bauhaus Weimar included Gerhard Marcks, Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky and László Moholy-Nagy.

Headline

In his manifesto and programme for the Weimar State Bauhaus, Walter Gropius called for a new beginning for building culture with elements that were considered visionary for that era. Art should once again serve a social role, and there should no longer be a division between the crafts-based disciplines. Instead of academic theory, the Bauhaus relied on a pluralistic educational concept, on creative methods and the individual development of the students’ artistic talents. Academic requirements for enrolment were dispensed with, so that talented young people could study at the Bauhaus Weimar irrespective of their educational background, gender or nationality. Between 150 and 200 students were registered at the Bauhaus Weimar. Depending on the semester, this included a 25 to 50 per cent ratio of women and a 17 to 33 per cent ratio of foreign students.

Headline

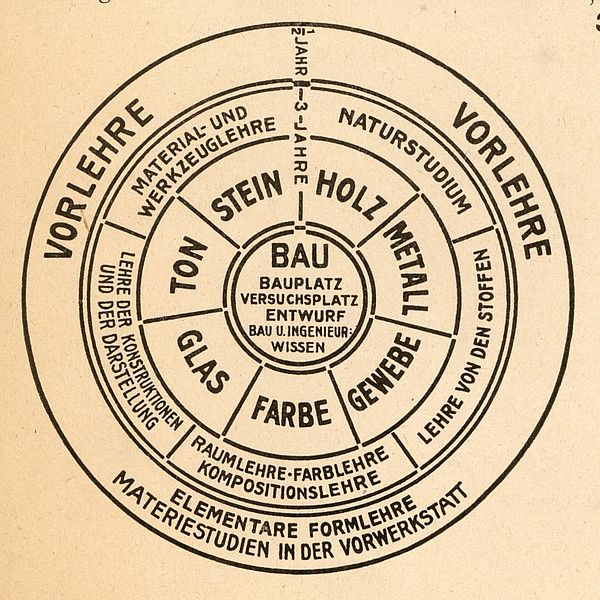

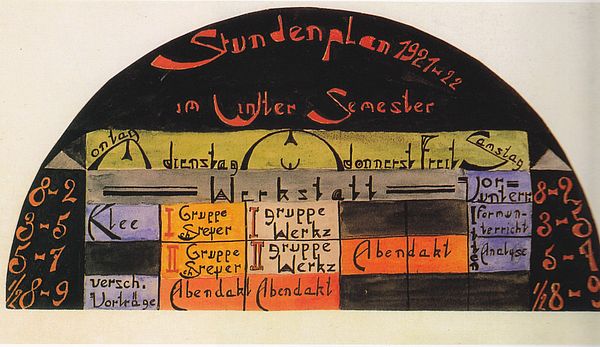

Based on the manifesto and programme of the Bauhaus, the Bauhaus masters in Weimar developed a new type of teaching programme based on the preliminary course developed by the Swiss artist and art teacher Johannes Itten, the famous form and colour theory of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky and practical training in the workshops. The ultimate goal of the educational programme was collaborative work on a representative building, the ‘Synthesis of the art’, as Gropius called it, to which all the Bauhaus workshops were to contribute.

Headline

The Bauhaus’s first publisher’s mark, the so-called Sternenmännchen (star mannequin) by Karl Peter Röhl, was designed in 1919 for a students’ competition and was replaced in 1922 by a design by Oskar Schlemmer. The new publisher’s mark was used to label the Bauhaus products and for all of the school’s important printed goods. Schlemmer’s impressive publisher’s mark is underpinned by the concept that the human being should stand at the centre of all the school’s endeavours.

Training in the workshops was preceded by the preliminary course, a trial semester where the personal skills of the students were tested and the foundations of craftsmanship and design were taught. Developed gradually up to 1921, the workshops were the centrepiece of the Bauhaus Weimar.

Headline

One special feature of education at the Bauhaus Weimar was the stage workshop, which was directed by Lothar Schreyer from 1921 to 1923 and Oskar Schlemmer from 1923 to 1925. The stage department was seen as an integrational workshop where the entire spectrum of visual and performing arts was fostered by an interdisciplinary approach.

Historically, the Bauhaus was more closely associated with the political, socio-economic and cultural developments of the Weimar Republic than any other German institute of education. The Bauhaus’s beginnings in Weimar were influenced by expressionism and, to a greater extent, the esoteric – largely thanks to Johannes Itten’s persona.

Headline

In 1923, Walter Gropius initiated a decisive change of direction at the Bauhaus Weimar. Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist, member and propagandist of the group De Stijl, served as a catalyst for this development, which was furthered by the confrontation with Constructivism and the demands of a technologically-orientated world. In this context, a pragmatic, functional approach prevailed – but this was not accepted without question at the Bauhaus. There is no doubt that this new direction triggered a rise in productivity as early as the Bauhaus’s Weimar phase, manifested in many design classics, such as the famous Bauhaus lamp by Jucker and Wagenfeld. The Bauhaus exhibition of 1923, which was the first major exhibition by the Bauhaus about the Bauhaus, was to convey this new direction to the public. The Haus am Horn was built in this context as the first architectural testimonial to the early Bauhaus in Weimar. It still exists today.

Headline

From its foundation, the Bauhaus was caught in the crossfire between different political parties. The right wing dismissed it as utopian and Bolshevist. The city’s populist nationalist politicians launched salvos against the school. Criticism also arose from the left wing spectrum for the first time. Between 1919 and 1923, the state government generally promoted Gropius’s plans. In the 1924 elections, the right wing party Thüringer Ordnungsbund gained a majority in the Landtag, the state legislative assembly. The budget for the Bauhaus was immediately cut by half and the teachers’ contracts cancelled as of 31st March 1925. In an act of self-assertion, Gropius and the Bauhaus masters resigned their posts in December. Various cities signalled an interest in providing a new home for the Bauhaus. Ultimately, the city of Dessau, which was governed by the Social Democratic Party of Germany, was favoured by the teachers due to its excellent economic perspectives.

After the move to Dessau in 1925, Walter Gropius donated 160 products made in the workshops of the Weimar State Bauhaus to the state’s collection. Weimar therefore possesses the oldest authorised Bauhaus collection worldwide.