Fine Arts

1923–1933

Although the Bauhaus did not see itself as an art school in the traditional sense, great importance was attached to the fine arts. Under Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, however, their influence was increasingly marginalised.

Meister und Lehrende

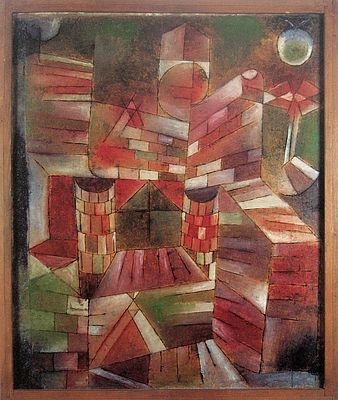

Paul Klee

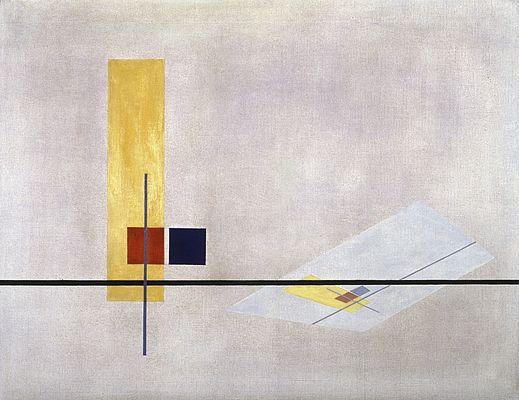

Wassily Kandinsky

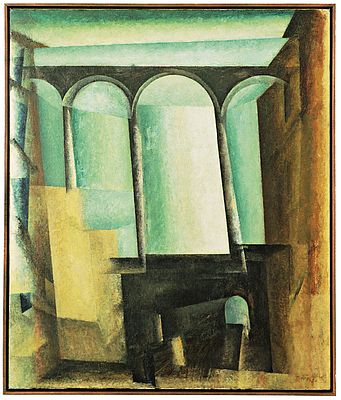

Fritz Kuhr

[Translate to English:] Headline

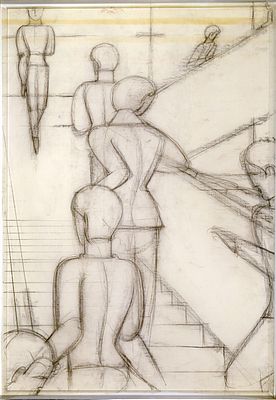

Free art, which was not bound to architecture, was recognised as a reservoir for new creative ideas at the Bauhaus – but it was not one of the subjects on the curriculum. In 1923, Walter Gropius wrote about 'modern painting, which has breached its historic boundaries, has generated countless ideas that are still waiting to be exploited by the practical world'. Gropius’s first employees were the sculptor Gerhard Marcks, the painter Lyonel Feininger and the artist and teacher Johannes Itten. Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Georg Muche, Oskar Schlemmer and László Moholy-Nagy joined them later. They taught the principles of design and were the artistic directors of the workshops. In this context, the masters were entirely free to decide on the content and character of the lessons.

In the early years, the Bauhaus was characterised by controversies about the value and role of art in the overall structure and educational programme of the school. The artists who were appointed at the very beginning, including Feininger, Muche and Marcks (but not Itten), primarily saw themselves functioning as personal role models. On the other hand, the masters appointed subsequently, such as Klee, Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy, recognised that the Bauhaus aspired to become a purpose-led academy and workplace that coordinated the arts and explored the laws of form and colour. At the same time, they did not want these principles to be mistaken as a recipe for the production of works of art. Instead, they wanted them to be seen as universally valid models for the elucidation and development of the various art disciplines. In the first Bauhaus magazine of 1926, Wassily Kandinsky explained the role, which the artists gave to teaching the principles of design: 'Painting is seen as a co-organising force.'

[Translate to English:] Headline

The establishment of the free painting classes in the winter semester of 1927–1928 heralded a new period of conflict. The progressive functionalisation and technological orientation of the workshops was countered by the intensified production of visual art. The visionary unity of art and design for a modern, more humane society began to dissolve. Ernst Kállai, editor of the Bauhaus magazine, stated at the end of the 1920s that there was a 'solely purpose-led and construction-orientated objectivity typified by mass production' on the one hand and a ‘metaphysical approach characterised by dream, vision, unequivocal spiritual belief or paradoxical acts of magic’ on the other.

The diversity of the artworks produced at the Bauhaus ranges from late expressionism and geometric-abstract works to the figurative works of New Objectivity or even Surrealism. There is certainly no unified ‘Bauhaus art’ or 'Bauhaus painting,' let alone a 'Bauhaus style'.