What exactly was the Bauhaus?

During its almost fourteen years of existence, the Bauhaus revolutionised creative and artistic thinking and work worldwide. The distinguished teachers who worked here included Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer, to name but a few. The following presents an overview of the most important developments. Detailed knowledge on the Bauhaus is available in the sections “Phases”, “Training”, “People” and “Works”.

1919–1925: The early years in Weimar

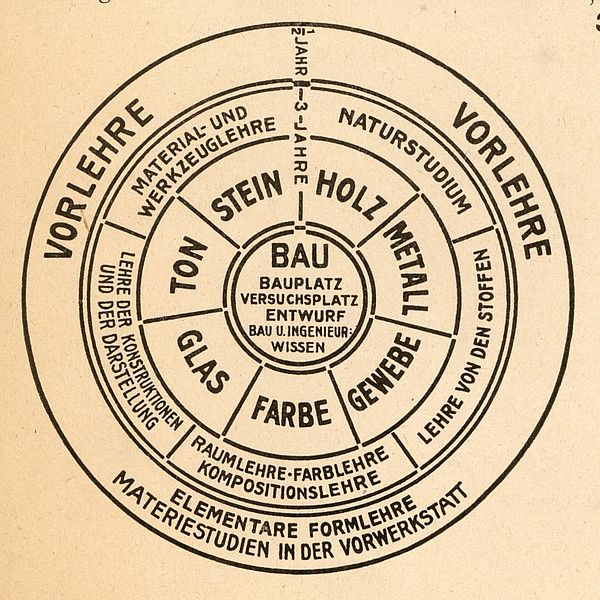

The Berlin-born architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919 as a school of design that worked along interdisciplinary lines, with an international outlook. Here, young artistically gifted men and women were to bring art, architecture and craftsmanship into optimal alliance and design the building as a synthesis of the arts. The diverse education began, at least in the early phase of the Bauhaus, with the preliminary course: Here, the Bauhaus students were taught how to work with materials based on educationally innovative and experimental methods.

Zwischenüberschrift

After that, the Bauhaus provided for a combination of teaching, practice and research. At the heart of the education of designers was experimentation and design in the Bauhaus workshops, where the divide between work and teaching was largely abolished. Each discipline had its own workshop: ceramic, weaving, carpentry, metal, printed graphics, stage, glass and wall painting. Each workshop had a master of works, who was responsible for craftsmanship and technical matters and a master of form, who took charge of aesthetic and creative aspects. Later in Dessau, photography and advertising workshops were added to these, as well as a formal course in architecture.

Walter Gropius employed a series of acclaimed artists as professors, among them not only Johannes Itten, Lyonel Feininger and Gerhard Marcks, but also Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky and László Moholy-Nagy. The Bauhaus Weimar thus became a meeting point for the international avant-garde. The workshops’ aim was to find applications for their work in the building; the Bauhaus remained true to this basic idea of an experimental laboratory for the building of the future, despite its many transformations, diversifications and reorganisations.

1925–1932: The Dessau years

Due to financial problems of political origin, in 1925 the Bauhaus left Weimar, the city in which it was founded, and relocated to the up-and-coming industrial town of Dessau. Dessau was tempting because of the prospect of realising Walter Gropius’s school building, now renowned worldwide as an icon of modernism, but even more so because the local industry promised a productive collaboration.

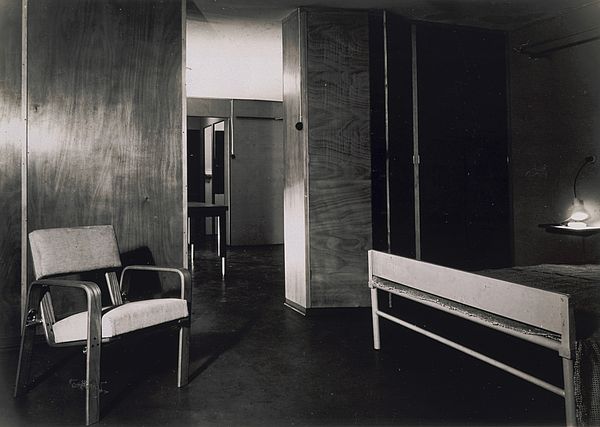

The Staatliche Bauhaus Weimar was rather expressionistic and artistic in its outlook, with some esoteric tendencies. At the school of design in Dessau by contrast, the maxim “Art and technology – a new unity” came to full fruition. From this point on, the focus was less on the individual work of art and more on the development of well designed everyday products, which were to be manufactured in association with industry. The majority of the best known products and buildings which continue to inform the image of the Bauhaus today were produced during this period, from Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture and Marianne Brandt’s ashtray to the best-selling product, the Bauhaus wallpaper.

Zwischenüberschrift

The theoretical lessons were now more broadly based and the teaching programme included other subjects such as, for instance, engineering, psychology or business studies. From this point on, the graduates completed their training at the Bauhaus with a Bauhaus Diploma. Almost all the notable Bauhaus masters moved with the school from Weimar to Dessau and as a result, the recently built complex of Masters’ Houses in Dessau became one of the most important artists’ colonies of the modern era.

Nonetheless, the meanwhile international reputation and many innovative buildings did not protect the Bauhaus Dessau from political hostilities, especially from the increasingly strong, reactionary right wing. In 1928 Gropius, unnerved by local political infighting, gave up his post and appointed Hannes Meyer, who had for a year been the head of the newly founded architecture course, as his successor. Meyer oversaw a reorientation of the Bauhaus, shifting the focus of schoolwork onto social ideals. Rather than being about great art, it was now first and foremost about science and the question of how affordable and well designed products and buildings could be made, or built, for all.

Zwischenüberschrift

Not only the “Volkswohnung” (People’s flat), but also above all the Laubenganghäuser (Houses with Balcony Access) on the experimental Dessau-Törten Estate and the ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau were architectonic examples of Meyer’s concept of collective design with a social objective. Once again, politics were responsible for ending Hannes Meyer’s period as director in 1930: Numerous students had become politically radicalised and engaged with communism. Meyer, himself a Marxist, was held responsible for this development and dismissed without notice.

On Gropius’s recommendation the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became the third Bauhaus director; Mies had among other things caused an international furore with his Barcelona Pavilion at the 1929 World Exhibition and was interested in one thing above all else: architecture and its aesthetic, without any palaver about art theory or social politics. As a consequence, even in its final phase the Bauhaus continued to change: The preliminary course was cast aside and the work in the workshops was reduced in form and significance and re-orientated to play a supporting role for contemporary architecture. Despite its depoliticisation, the Bauhaus Dessau was forced to close on 30 September 1932 by the National Socialist majority in Dessau’s city council in a move fuelled by longstanding opponents of the Bauhaus, such as Paul Schultze-Naumburg.

1932–33: From Berlin into the world

For a single semester, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe attempted to keep the Bauhaus going as a private institution in an old telephone factory in Berlin-Steglitz. But from April 1933 the National Socialists, by sealing the building, stopping the teaching staff’s pay and ultimately by cancelling the tenancy agreement brought about the final collapse of the Bauhaus, the dissolution of which was announced in a circular by the third and last director on 10 August 1933.

Thus the school was brought to an end – though its ideas lived on. Many Bauhauslers went into exile and contributed, along with the many international students returning to 29 different countries, to the dissemination of the Bauhaus throughout the world: whether in the successor institutions such as the New Bauhaus in Chicago or the Black Mountain College in the forests of North Carolina, in the White City in Tel Aviv, built in the international style, or in the collection of the MoMA, New York, whose founding director, Alfred H. Barr, was an advocate of the Bauhaus who exhibited photography, design and architecture alongside the classical arts.

Headline

There is however no such thing as a consistent Bauhaus style – the Bauhaus was far too diverse and heterogeneous for that. This is precisely what makes it still so interesting and contemporary today: The Bauhaus was an interdisciplinary, international workshop for ideas, in which diverse opinions, theories and styles coalesced in the search for the New Man, New Architecture and New Living; in which the primary focus was on an open-minded approach to methods and ideas: namely, on reinventing the world.

[AG/GB 2016]